Kelp Forest as Ocean Welcome

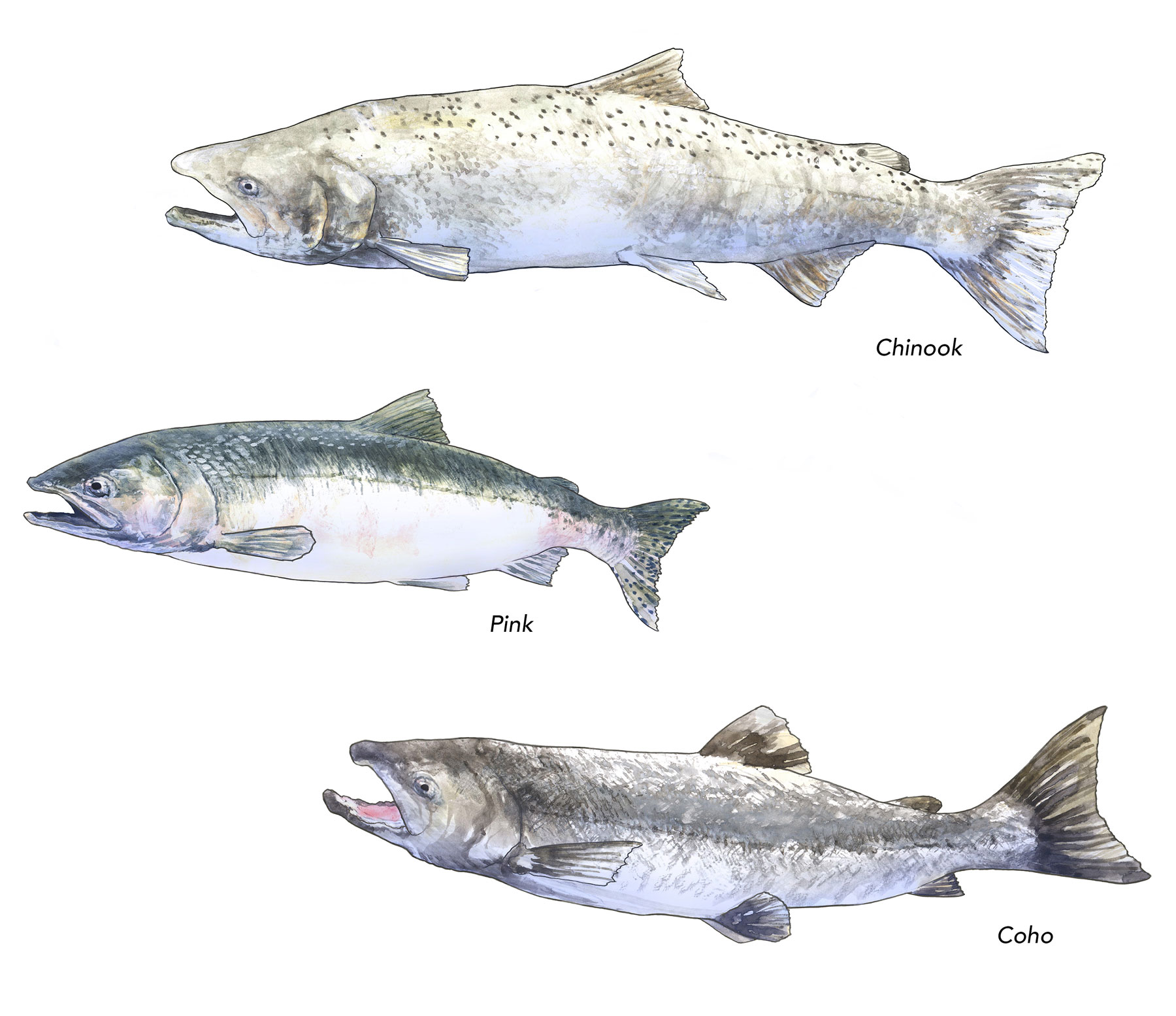

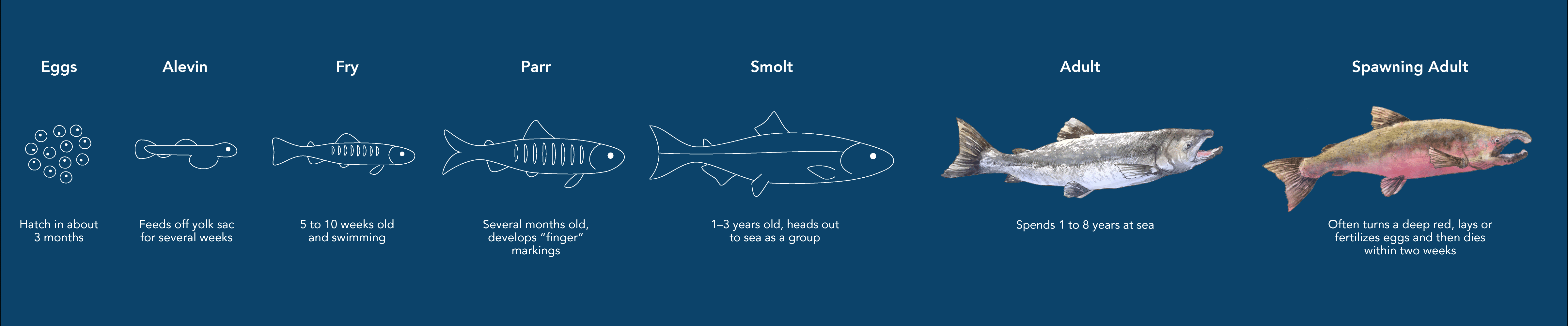

Sockeye, pink, coho, chum, and Chinook make a lovely alliterative list of the five salmon species (genus Oncorhynchus) found up and down the waterways, both fresh and salty, of the Pacific Northwest and Alaska. The iconic fish that Indigenous Tribes and First Nations have revered since time immemorial, that sport fishers pride themselves on hooking, and that most Americans assume can land on their dinner plate, has a remarkable life history from its birth far up freshwater streams, out into the open ocean, and back again to die after spawning in their natal waters. Salmon are anadromous—they transition from freshwater to salt water—and their transition into the marine environment is where the kelp forest and salmon stories entwines. This is a story being written by scientists right now. While there are many visual accounts of “tons of salmonids in the kelp beds!” there is very little data to quantify this relationship. Those who study and dive in the bull kelp forest, those who see seals break the surface from the kelp beds with an orange blur thrashing in the waves, those who count salmon prey and gauge fisheries health, know that the bull kelp forests provide habitat and migratory protection for salmon. But recording this is another challenge. Alaska is ground zero for this new science. Using more advanced GoPro timelapse videography, water sampled for eDNA, and SMURFS (a stacked lantern-like cage apparatus) to capture fish, data is being collected from wild bull kelp beds as well as from within bull kelp farms to quantify the salmon-bull kelp connection.

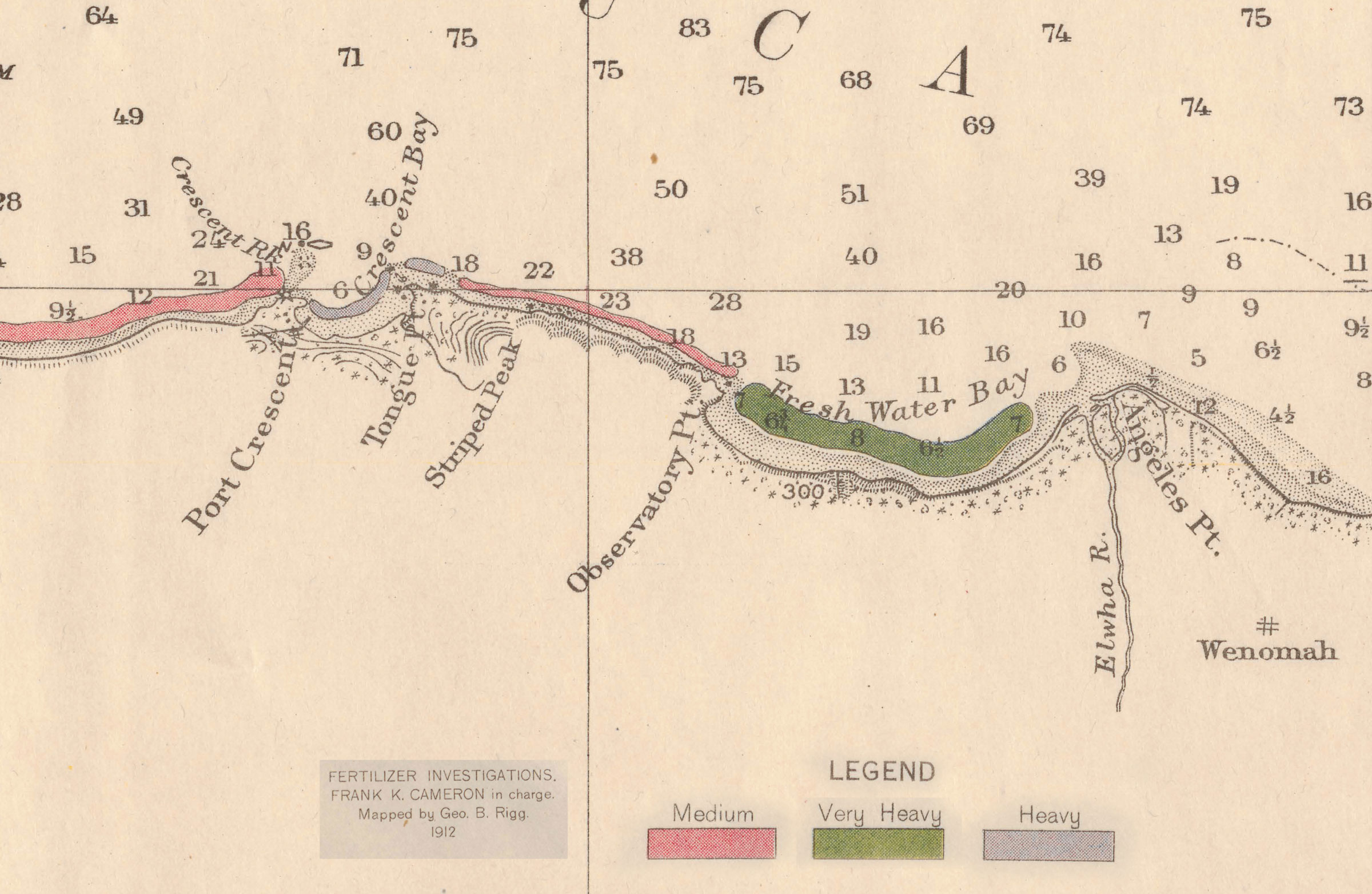

Each salmon species has a different timing on when they emerge from their birth rivers through estuaries and out into the ocean. Pinks are the smallest and most common salmon and have a life cycle of only a couple of years, so they emerge quickly. King, or Chinook salmon, are on the other end of the spectrum being the largest and longest lived. They might spend from one to three years in the rivers before entering the ocean. Bull kelp likes the ocean waters adjacent to river openings [see the Oregon Coast regional page] which gives young salmon emerging from the rivers a chance to hang out in the kelp forest and adapt to the ocean.