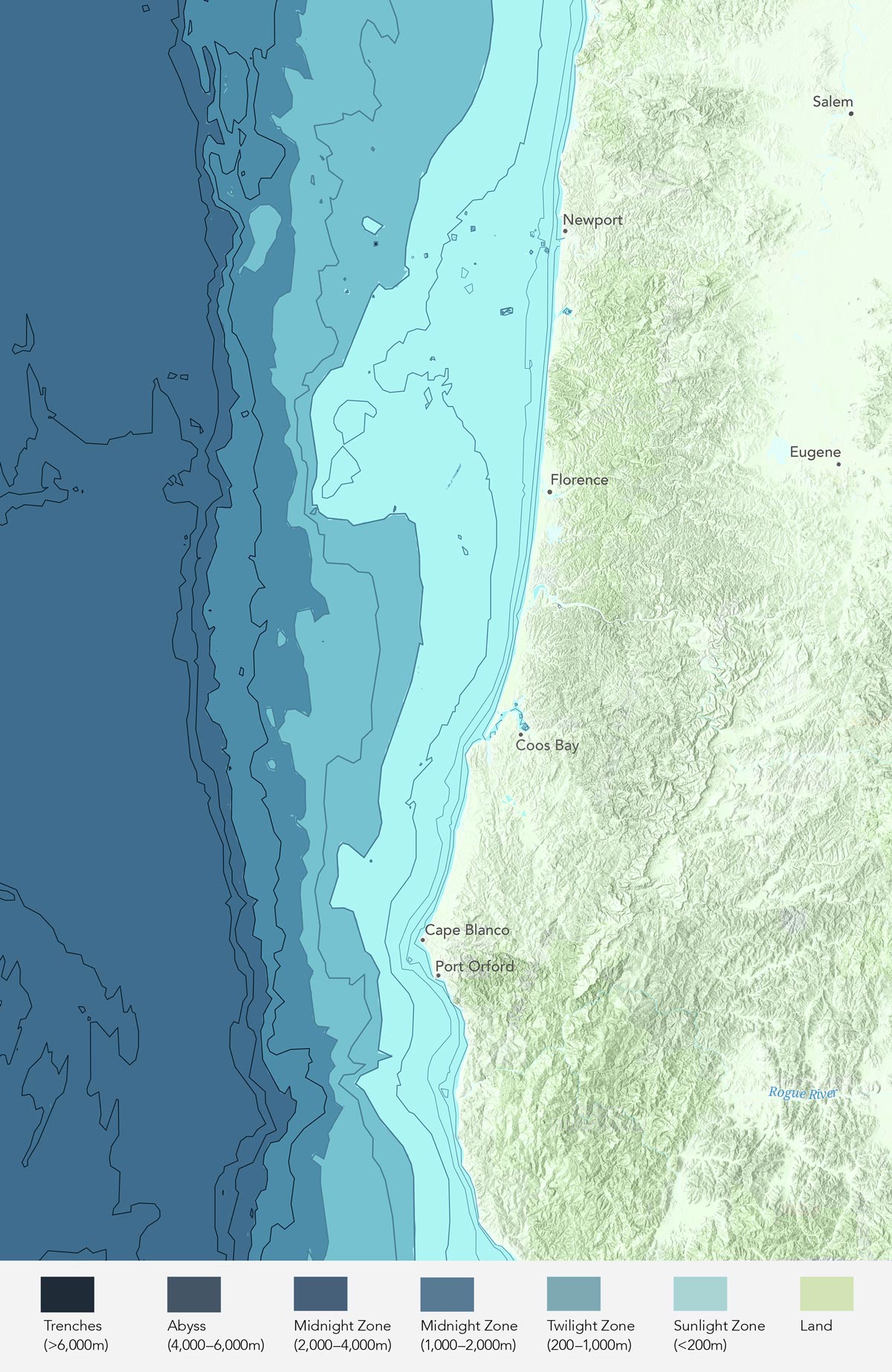

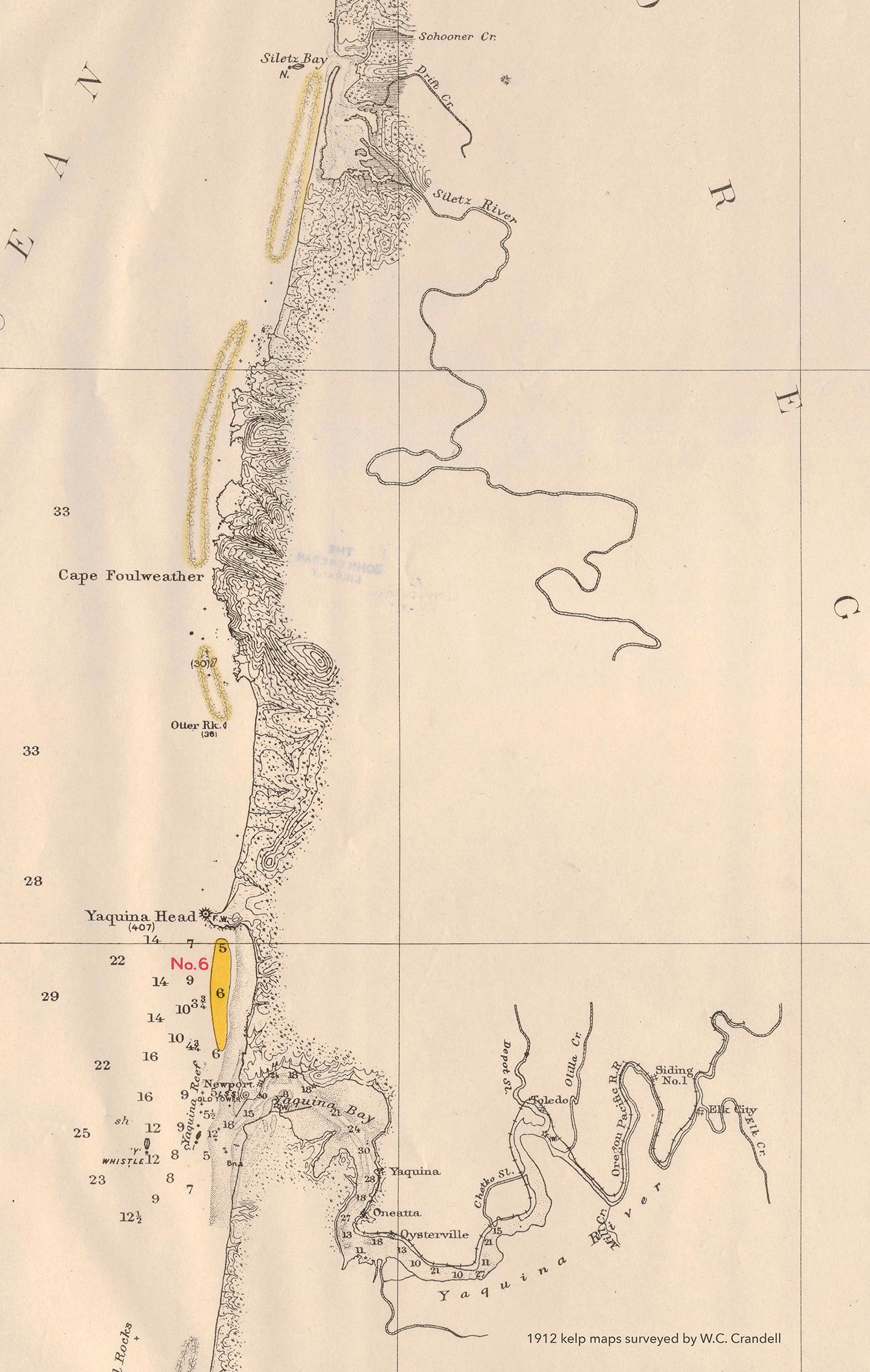

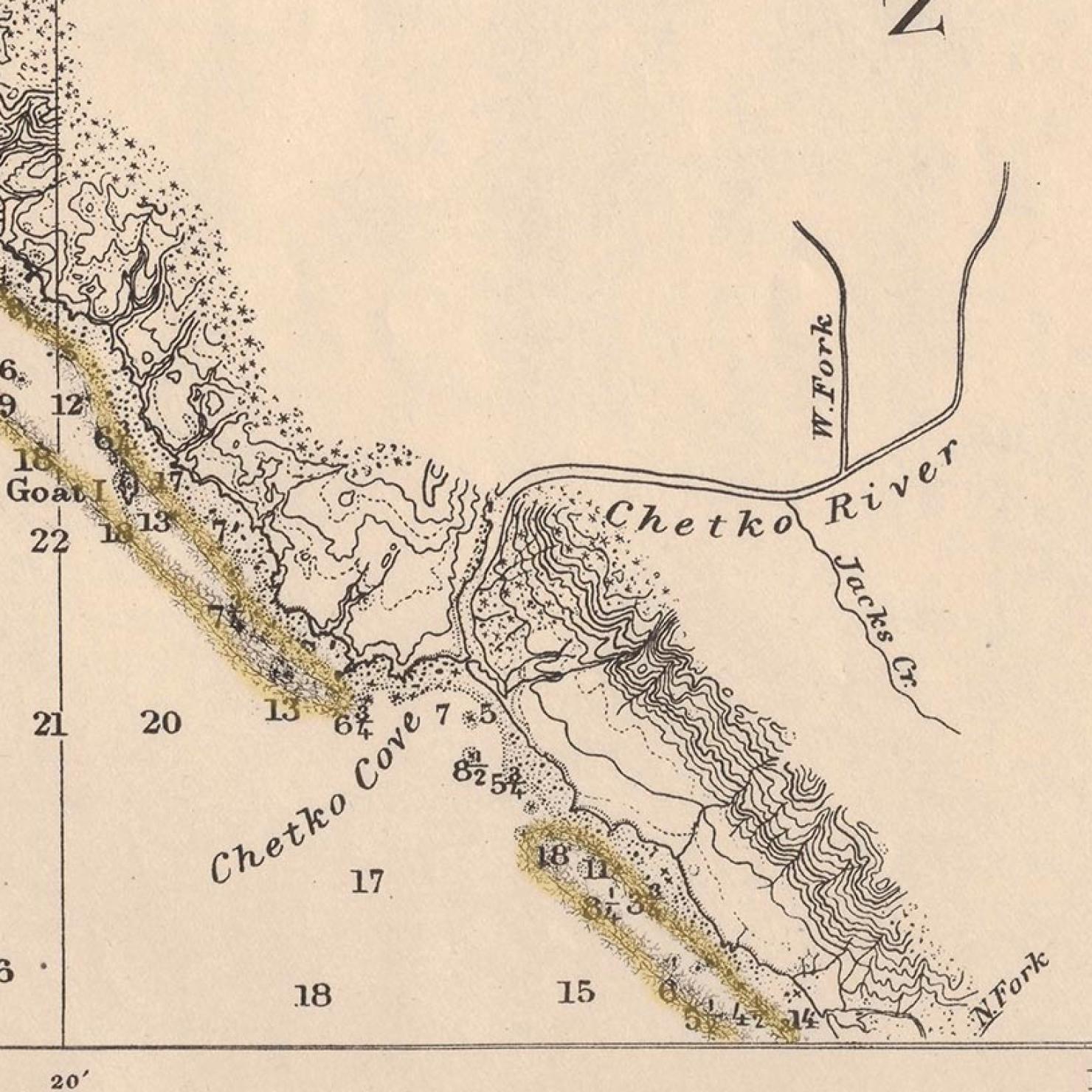

The Oregon Coast is full of contradictions: It has amazing rocky reefs, perfect bull kelp habitat, but it also has long expanses of sandy shore and sandy beaches, not kelp habitat at all. Its coast is stunning and wild and full of life, yet only a tiny portion of it, less than two percent, is protected in five distinct marine reserves surrounded by marine protected areas, positioned almost equidistant from each other along the coast. The salty Pacific Ocean is interrupted by the outflow of seven great rivers along this Oregon stretch, bringing great quantities of fresh water to mix with the salt. Oregon’s fisheries are intense commercial enterprises, pulling crab, rockfish, and urchin out of the coastal waters, and yet the fishers are often the front line observers of ocean change. There are two coastal landmarks named for sea otters, Otter Rock and Otter Point, and yet there are no sea otters on the Oregon coast. Even looking locally at the southern coast around Port Orford in 2023, observations of bull kelp offer a tale of two reefs: sustained kelp beds at Rogue River Reef but kelp beds transformed to urchin barren just to the north at Orford Reef.

These contrasts illustrate the profound variety of ocean conditions found along the sparsely populated Oregon Coast, and the points of potential bull kelp abundance are out of sight, and not aligned with where people live. This makes telling the bull kelp story all the more difficult and important.