A Keystone Predator

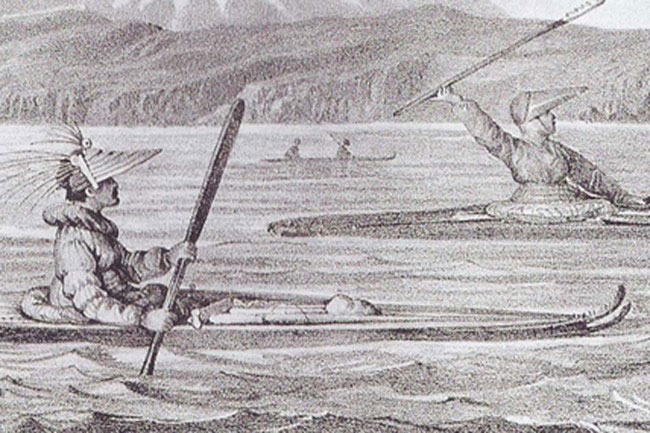

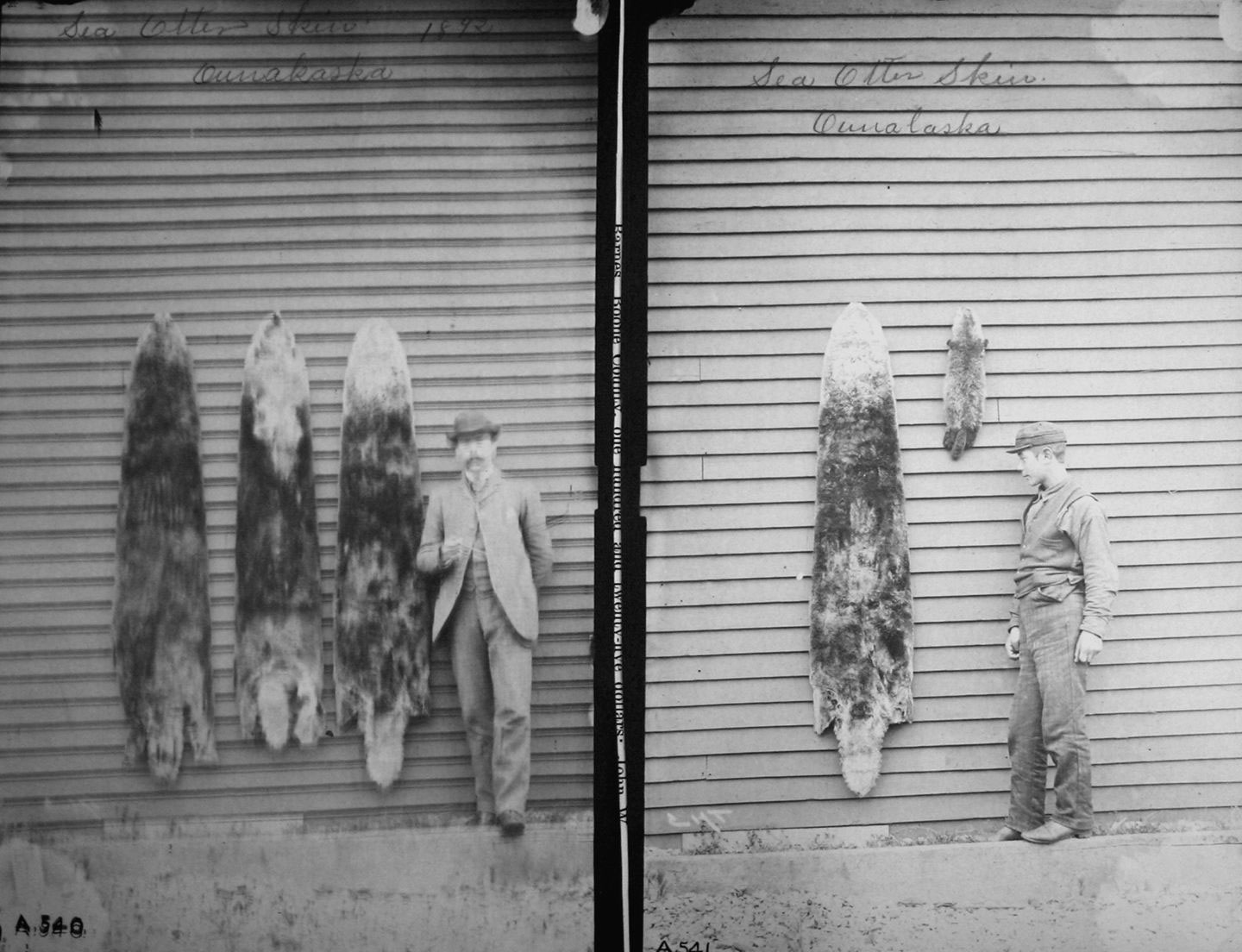

Sea otters have historically been part of the kelp forest ecology of our Northern Pacific Ocean. Prior to 1740, when the 2nd Bering expedition set out from eastern Russia to explore the Aleutian chain of islands and find America, it is estimated that around 300,000 sea otters populated their entire range skirting the North Pacific Ocean, from the very northern tip of Japan, along the Aleutian Islands down the coast of Alaska and British Columbia and continuing south through Washington, Oregon and California to Baja California in Mexico. This is not a large number of marine mammals in total, but sea otters are individually impactful—each otter contributes significantly to the ecosystem in which it inhabits. Sea otters are voracious top predators, their favorite prey are sea urchins, clams, abalone, crab and other mollusks as well as sea cucumbers. They are associated with the kelp beds they live within, keeping the urchin grazer in control so the kelp beds and the richness of life they support can thrive. They are a quintessential “keystone species,” affecting food webs beyond themselves. Like other top predators, otters provide resilience to the near shore ocean systems they live within.