Helping the Kelp!

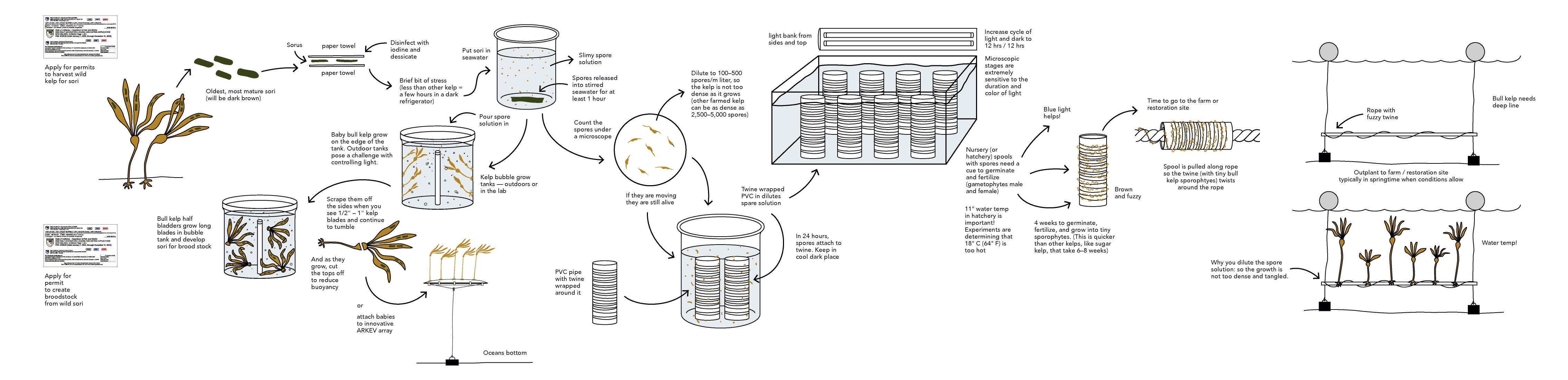

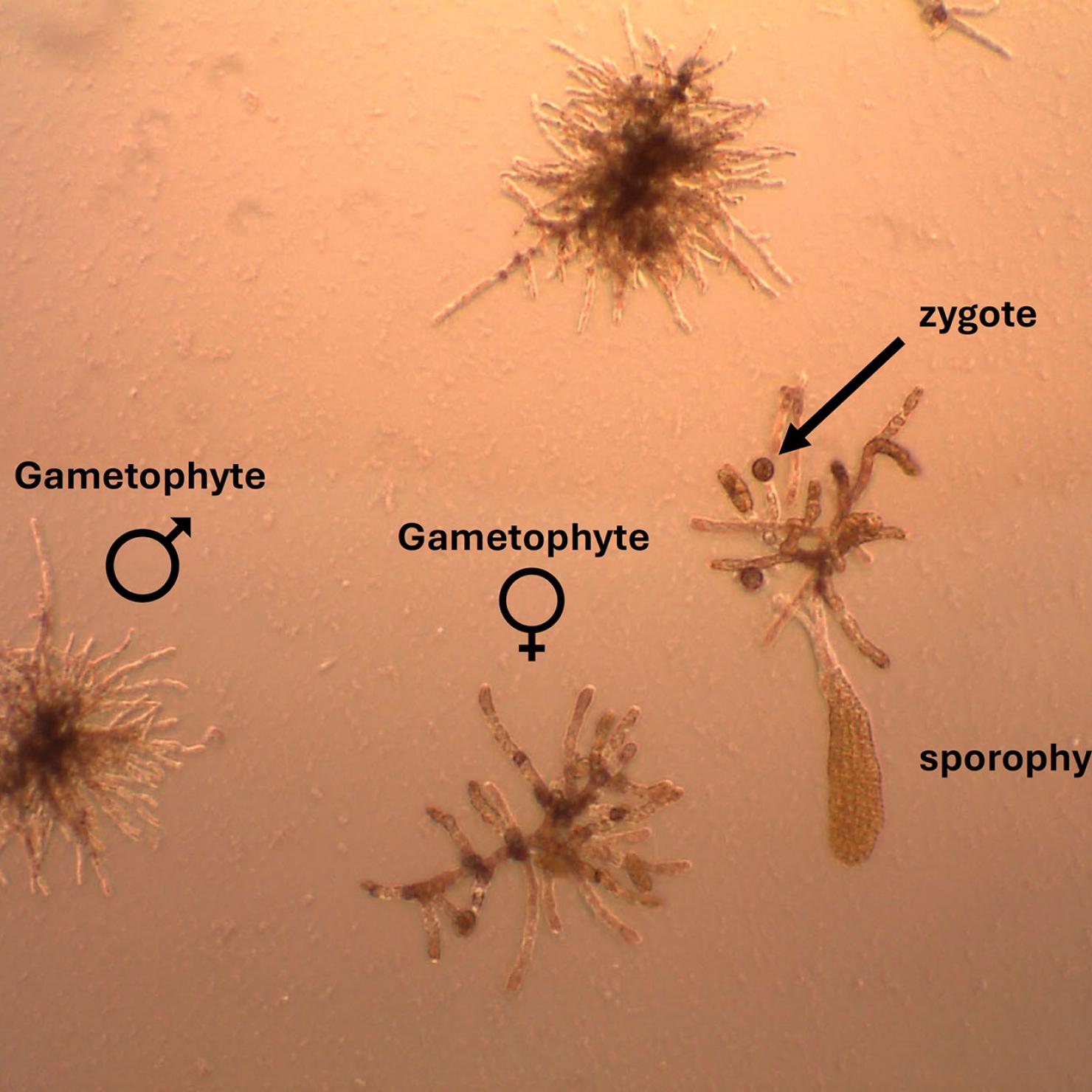

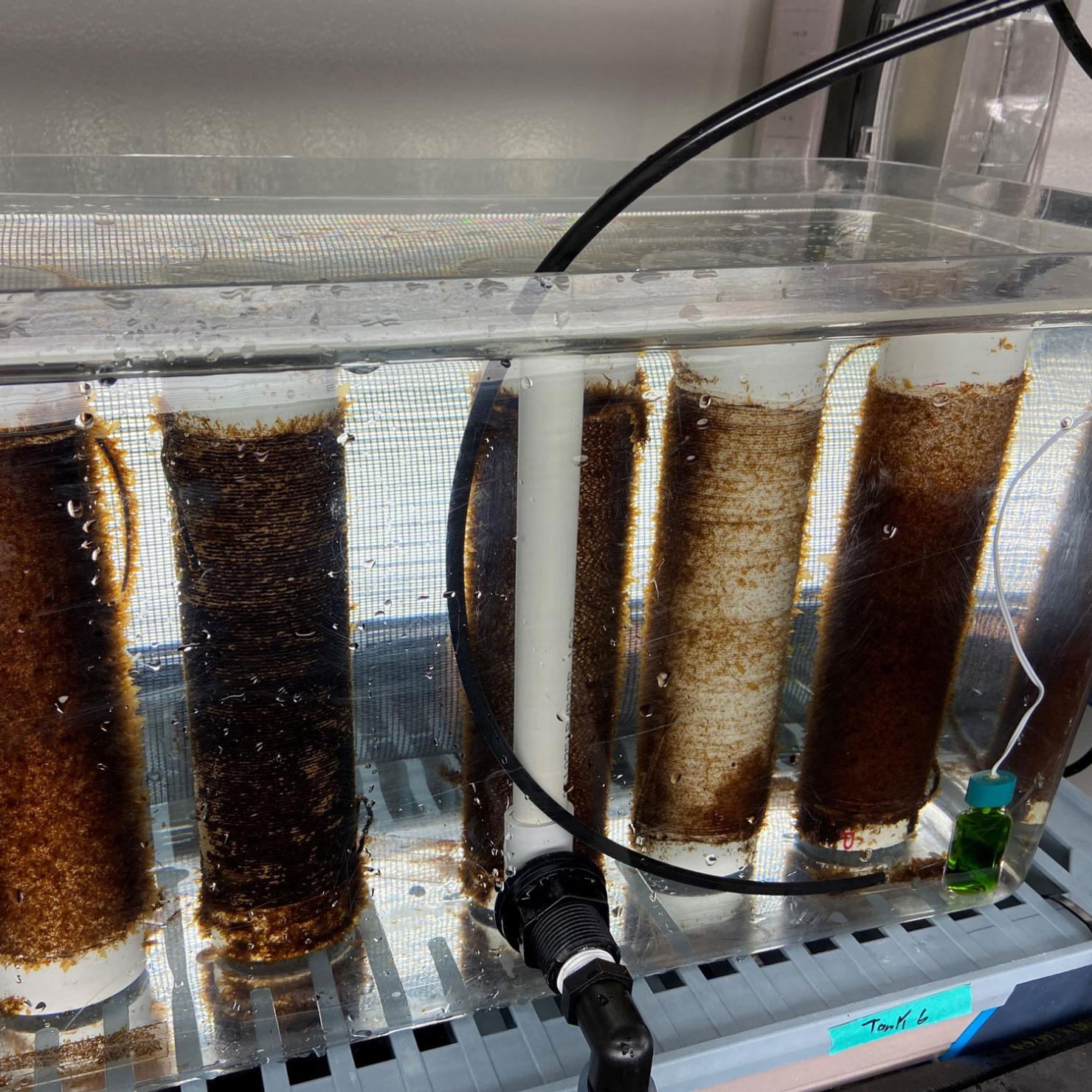

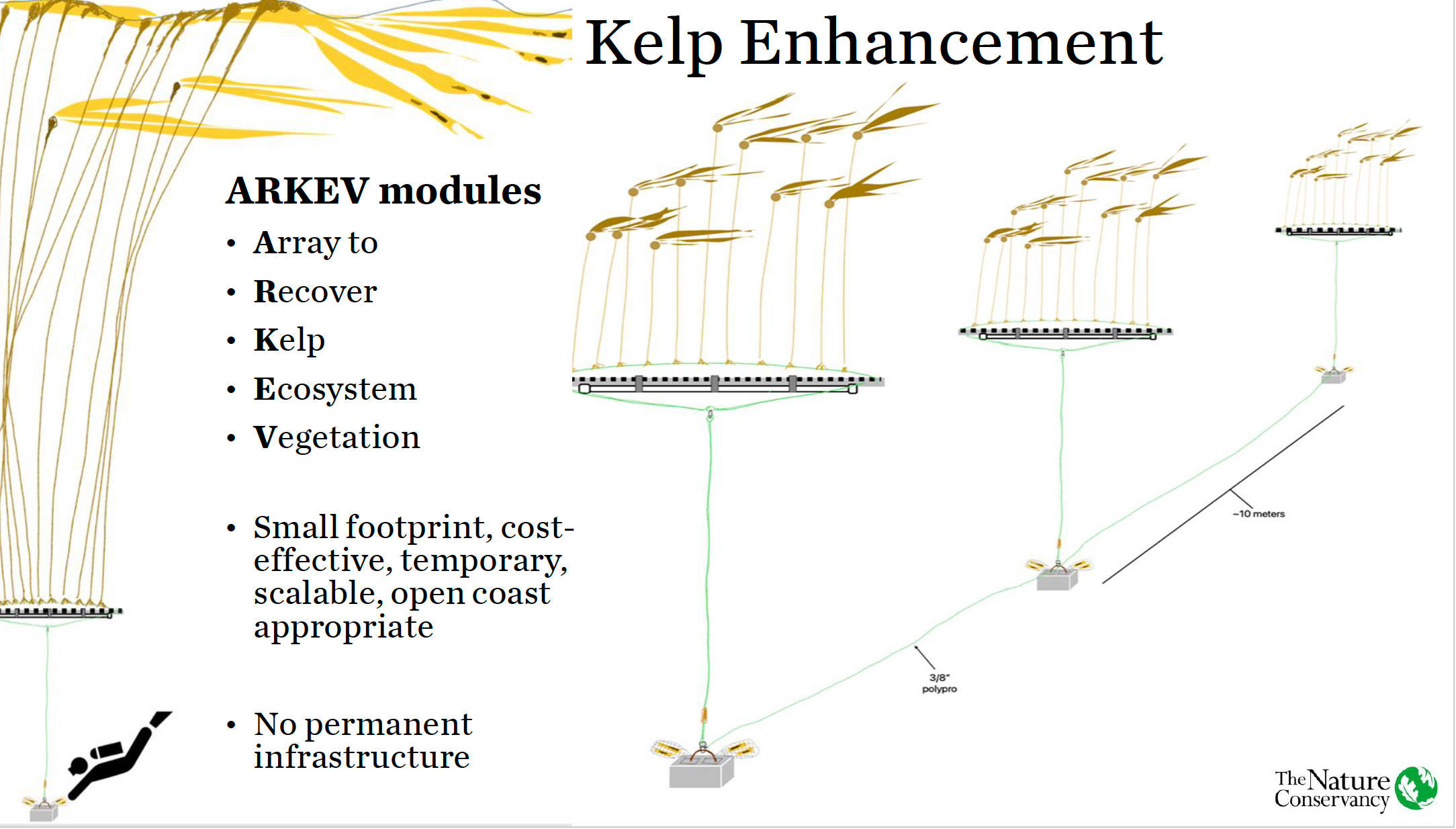

The extreme loss of bull kelp from historic beds along the Northern California Coast, as well as in Oregon, Puget Sound, and the Salish Sea waters, has made helping its recovery an urgent mission for scientists, Tribes, and communities alike. Kelp forests globally have been recognized as crucial for ocean biodiversity and health, and their decline in as far-flung places as southern Australia, coastal Portugal, or northern Norway has inspired kelp restoration efforts worldwide. The Global Kelp Alliance is tracking these efforts project by project and is a fantastic resource. The techniques and methods for each kelp recovery project target an endemic kelp species and involve the combination of a unique ecological drama with a unique combination of stakeholder communities. The edge of the Northeast Pacific Ocean, however, where bull kelp, or Nereocystis leutkeana, grows, presents particular challenges to kelp recovery teams: the water is freezing, the ocean rough, with low-visibility, and it is scary (there are sharks, and the coastal access difficult). Limited diver availability and a timing and seasonality to this particular species make restoring bull kelp forests tricky. As an annual, large bull kelp sporophytes are only present for part of the year, and restoration out plantings need to coordinate with bull kelp’s natural growing cycles.