Sunflower Sea Star

Sunflower sea star

Pycnopodia helianthoides

Wolves of the Sea

The sunflower sea star, Pycnopodia helianthoides, is deeply connected to the bull kelp forests of the north Pacific. Its biogeography matches bull kelp almost precisely, ranging from the middle of the Aleutian Islands down through the Pacific Northwest and California to become rare south of Monterey. Pycnopodia is not one of the sea stars we find among the rocks at low tide; it inhabits the deeper waters. The most common stars found in the intertidal zone is the ochre star, or Pisaster ochraceus, the purple or orange five-armed starfish with bony white patterns on its surface. There are also bright orange bat stars and leather stars in the intertidal. A coast-wide “Solstice Sea Star Search” bioblitz on December 21st 2022, had sea star lovers out at the extreme low tides from San Diego to Crescent City, California. They found 1,874 ochre stars, 580 bat stars and 100 leather stars. They found no sunflower sea stars.

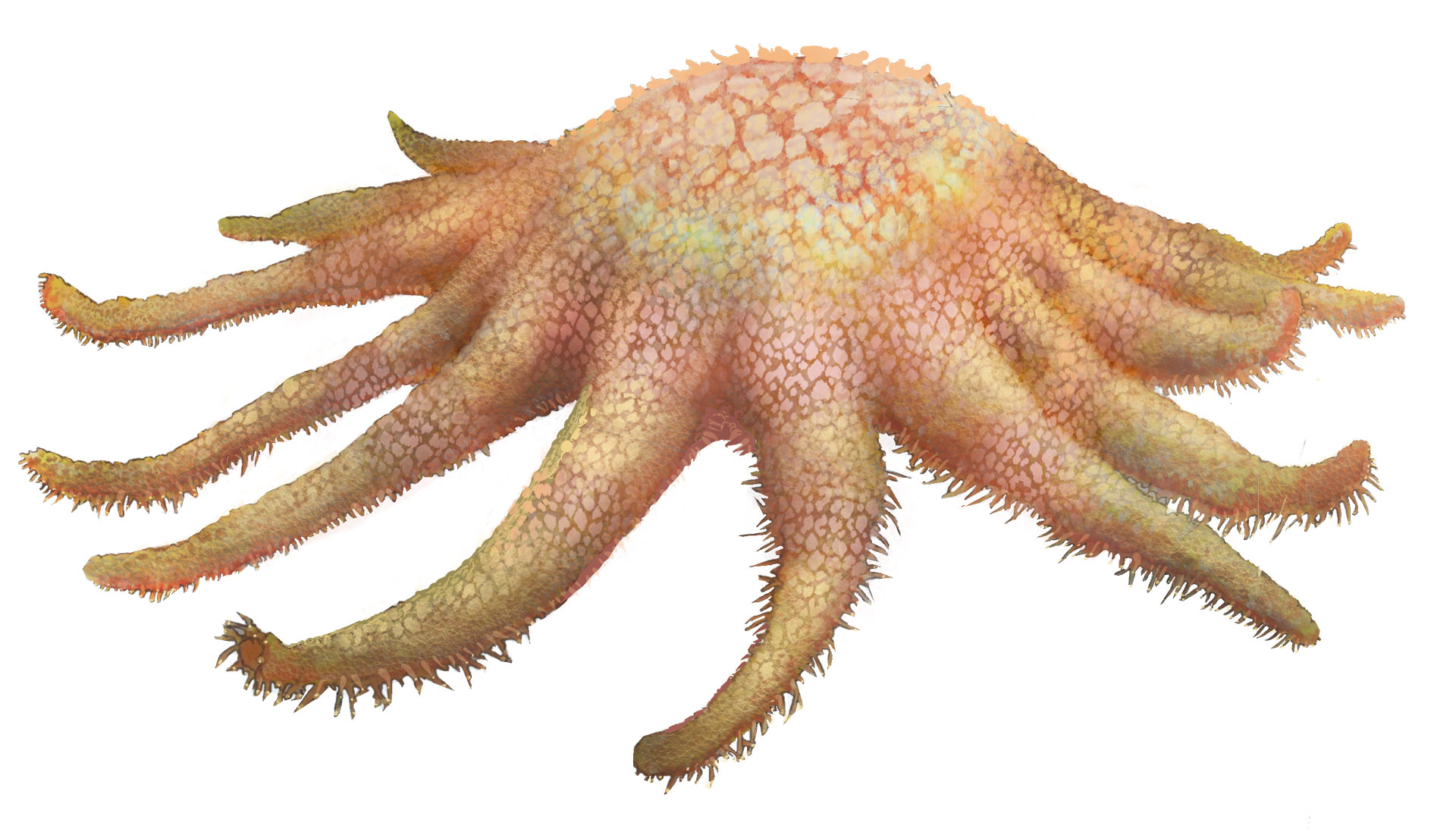

Sunflower sea stars are the deep water “wolves” of the sea—as big as a pizza—with 15–24 arms radiating out from a large fleshy middle. They are known as “ragmops” by fishermen when they are brought up as bycatch, for obvious reasons. They are vibrantly colorful ranging from reddish-orange, purplish, yellow or violet-brown on the top side and sport over 15,000 suctioned tube feet on its bottom side. They move swiftly (for a sea star) on these tube feet to swarm over and eat other invertebrates, both alive and dead, living in their ocean bottom habitat. They can sense light and dark and chemical cues guide them towards a food source. Their favorite prey is sea urchin which can make up almost all of their diet. They are an impressive predator, and, in the absence of sea otter in the kelp forests, they can keep urchin populations in check, maintaining these thriving habitats of biodiversity.

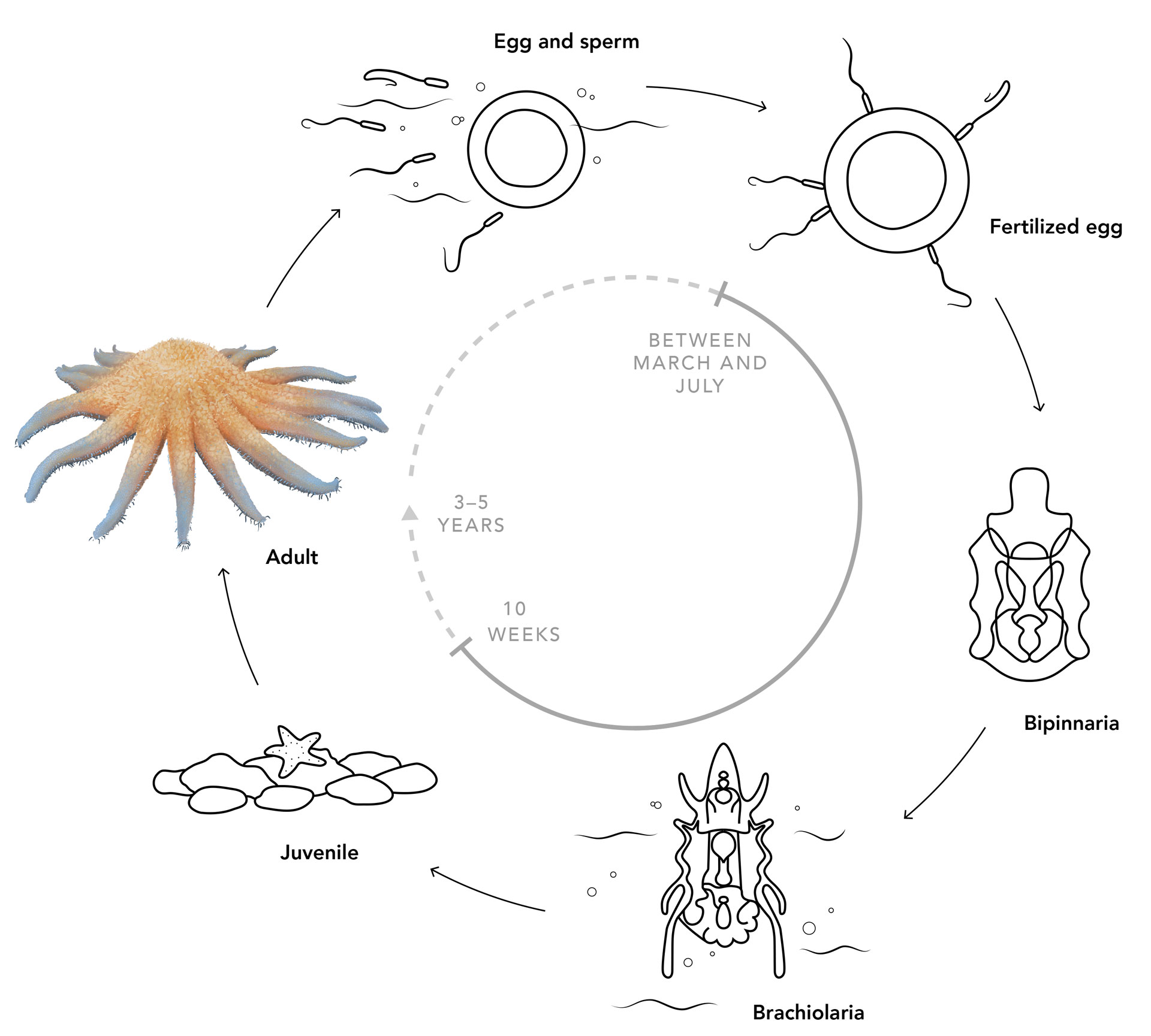

Sunflower sea star life cycle: from planktonic larvae to tiny juvenile with five legs to 24"-wide, 20-armed, soft-tissued hunter.

Pycnopodia are in the class Asteroidea and like their sea urchin cousin, they are broadcast spawners. It is unclear exactly how often and when Pycnopodia spawn, but it has been observed that during the peak months of May and June the males and females each release their egg or sperm into the water column where fertilization happens by chance. The fertilized egg develops into a bilaterally symmetrical arabesque of a larvae, swimming in the water column, living as plankton for two to ten weeks. After settling on the bottom the larvae metamorphose into a tiny sea stars as big as a pinhead with five perfect rays. As they grow these juvenile stars become efficient predators, eating juvenile urchin at a rate of four or five a day. It is surmised that these juveniles can be perhaps more important than the adults at keeping urchin populations down, as adult sea stars will eat only one larger urchin a day. As the sea star grows it adds rays in between the existing legs. If a Pycnopodia loses a leg it can grow it back. It can even regenerate an entire body from a single leg, if some of the central portion is attached.

Redundancy at the Top

The bull kelp forests of the North Pacific evolved with two urchin predators doing their work to maintain ecological balance: the sea otter and the sunflower sea star. Redundancy at the top of the trophic cascade is often the norm, adding resilience and stability to an ecosystem: think wolves and bears in Yellowstone. When sea otter were extirpated in the early 1800s along the Pacific coast, sunflower sea stars not only preyed on sea urchin but elicited a behavioral response from urchin to stay hidden, and kelp forests maintained viability but lost resilience. Sea otter have returned to some areas of Alaska and British Columbia so the relationship between these two mesopredators of the kelp forest could be studied. Jenn Burt et al., found that otter and sunflower sea stars go after different urchins, creating a greater buffer against urchin barrens with two predators at work rather than one. Otter are pretty picky about what they will eat, only choosing urchin that offer the caloric benefits they need, i.e. the big and juicy ones. Sunflower sea stars, on the other hand, will forage for the smaller urchin that otter will leave behind, playing clean-up crew. Both turn out to have an enormous impact on the kelp forest.

The importance of redundancy was driven home in 2014 when Sea Star Wasting Disease wiped out almost every single sea star along the West Coast of North America. With resiliency already compromised by the extirpation of the sea otter, many kelp forests along the coast were left with no urchin predator at all. Freed from predation by the hunter seastar, urchin populations came out of the cracks and started eating down the kelp, increasing their numbers by 60-fold in some regions. The regime shift from kelp forest to urchin barren was a quick switch.

Sunflower sea star, before and after sea star wasting disease

5.75 Billion Sunflower Sea Stars—Gone

There is a remarkable picture of an underwater rock carpeted with hundreds of velvety sunflower sea stars. The date is October 9th 2013. A follow-up photograph taken of the same rock on October 29th shows completely barren rock. The sea stars are gone. They have melted away.

From the Aleutian Islands to Baja California, sea stars of all kinds developed white lesions and, literally, melted away within hours as the sea star wasting disease spread through the ocean water in the new year of 2014. Billions of armed organisms, vanished. The sunflower sea stars, whose populations were previously robust—as one diver said, like seeing robins in the neighborhood, were hit particularly hard. The ochre and bat stars have recovered quickly. Over a decade later, it has been determined that a variant of a relatively common bacterium, Vibrio, specifically Vibrio pectenicida, is the culprit causing Pycnopodia’s body to melt away. In June 2024, a juvenile sunflower star was spotted in the tidepools along the Mendocino headlands. The photograph of the tiny multi-armed star went viral on the internet. A Pycnopodia on the North Coast! Farther north, however, recovery seems in progress. Sunflower sea stars are not uncommon to find in northern BC waters or in Alaska, but as functioning elements in the bull kelp forest ecology below Vancouver Island, they are gone.

How Old is this Sea Star?

Like seaweeds and kelp, starfish do not have a calcified shell to fossilize, so like seaweeds, they are not included in the archaeological record. Also, it is virtually impossible to tell a sea star’s age. It is thought that sunflower sea stars can live to be 20–65 years old.

A Perfect Storm

The years 2014–16 mark a confluence of events that affected the bull kelp forests so drastically that we can use this point along a timeline to demarcate a before and after in terms of bull kelp health. The Sea Star Wasting Disease was accompanied by an ocean heat wave—an intensely warm “blob” of ocean water that raised the temperature in the open Pacific off of North America by almost 2.5 degrees C. This warm blob was exacerbated by the periodic ocean warming of an El Niño cycle in 2015–2016. Bull kelp needs cold nutrient-rich oceans to thrive. The nutrient-poor, warmer water of the blob, combined with the intense grazing of the exploding urchin population created a “perfect storm” of stressors on the kelp. Very quickly the bull kelp was mown down by the urchin hordes, so that the historic bio-diverse kelp beds of Sonoma and Mendocino Counties were reduced to impoverished urchin barrens. A year or so later the same shift was seen by divers to the north along the Oregon Coast at Port Orford. To the south in Monterey, even with sea otter in the mix, patches of kelp forest were devastated by urchin grazing.

The Pycnopodia are missed in California and Oregon! Their essential role in holding a fragile ecology in place was underscored when multiple stressors came to bear on the kelp forest in such a compressed time-period.

The sunflower sea star has been listed as critically endangered by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature. While the culprit creating the wasting disease has been found—a tiny bacterium in the same family of bacteria that causes Cholera in humans—the sunflower stars in California and Oregon have not returned. Except…in the lab.

Diagram of participants in the complex process of breeding and raising young Pycnopodia. This collaboration, initiated by The Nature Conservancy, involves labs up and down the West Coast and as far afield as Nebraska.

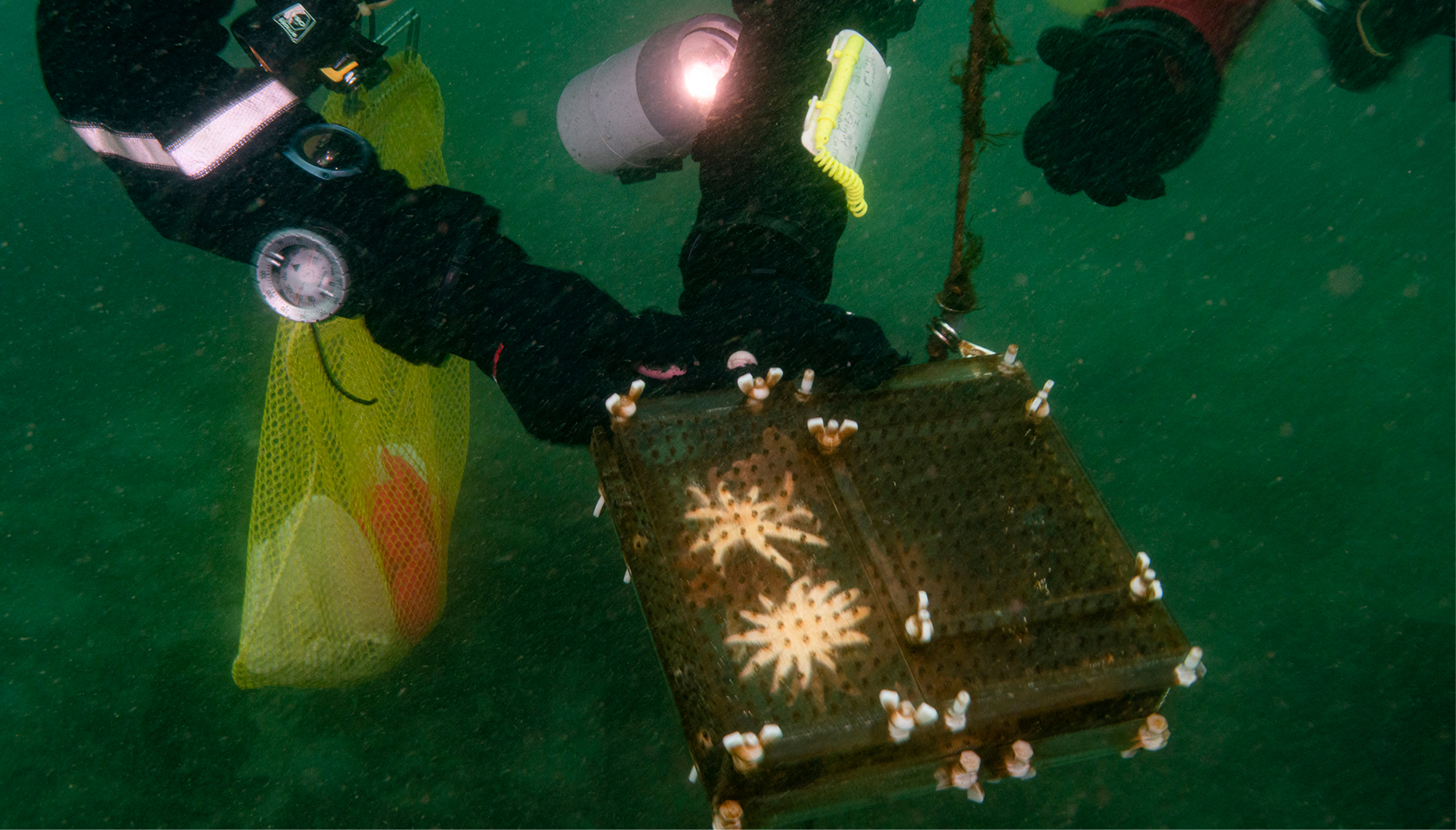

Can sunflower sea stars be raised in a tank?

Jason Hodin at Friday Harbor Labs on San Juan Island Washington broke new territory in breeding sunflower sea stars in the lab. As of February, 2023 he had 109 one-year-olds, 23 two-year-olds, 12 three-year-olds, and 5,000 larvae in the tanks, all bred from sixteen adult sunflower sea stars found from painstaking scuba searches around Puget Sound. A one-month-old baby sea star is the size of a poppy seed! A one-year-old starfish is barely an inch across, and just budding extra rays out between its initial five rays or ‘podia’, but its sensory tube feet are madly active, sensing the world around it. Keeping these tiny beings alive in tanks is a learning process that The Nature Conservancy and SAFE (Saving Animals from Extinction) have spearheaded in partnership with a variety of research institutions and the establishment of the Sunflower Star Laboratory at Moss Landing. A massive team of scientists and educators from zoos, aquariums, and research labs has raised a generation of sea star siblings. A single pair of stars spawned successfully at the Birch Aquarium in San Diego in late 2023, resulting in millions of larvae, that have now grown in nine different labs across the West Coast and are exhibited in various aquariums. Scientists are analyzing the genetics of these lab-raised stars and noting their feeding habits. Tiny juvenile Pycno eat tiny juvenile sea urchins—lots of them!—illustrating an added superpower in controlling urchin densities. Now (August 2025) that the causative agent of Sea Star Wasting Disease is known, the bacterium Vibrio pectenicida, that too can go into the research and planning around re-introduction of lab-raised sea stars. Researchers hope that, someday, these young sunflower sea stars will be released into the wild to resume their role as top predators of urchins.