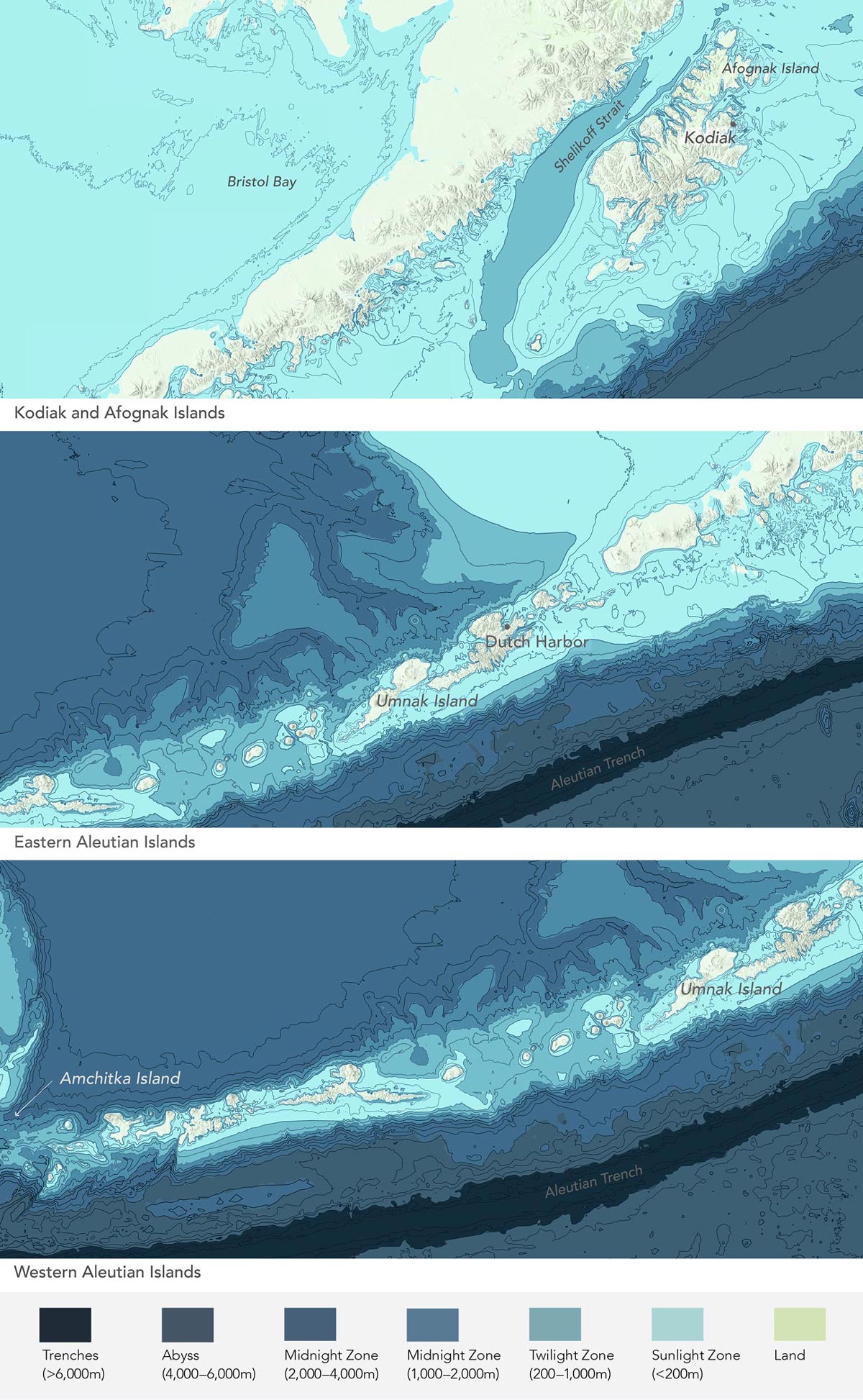

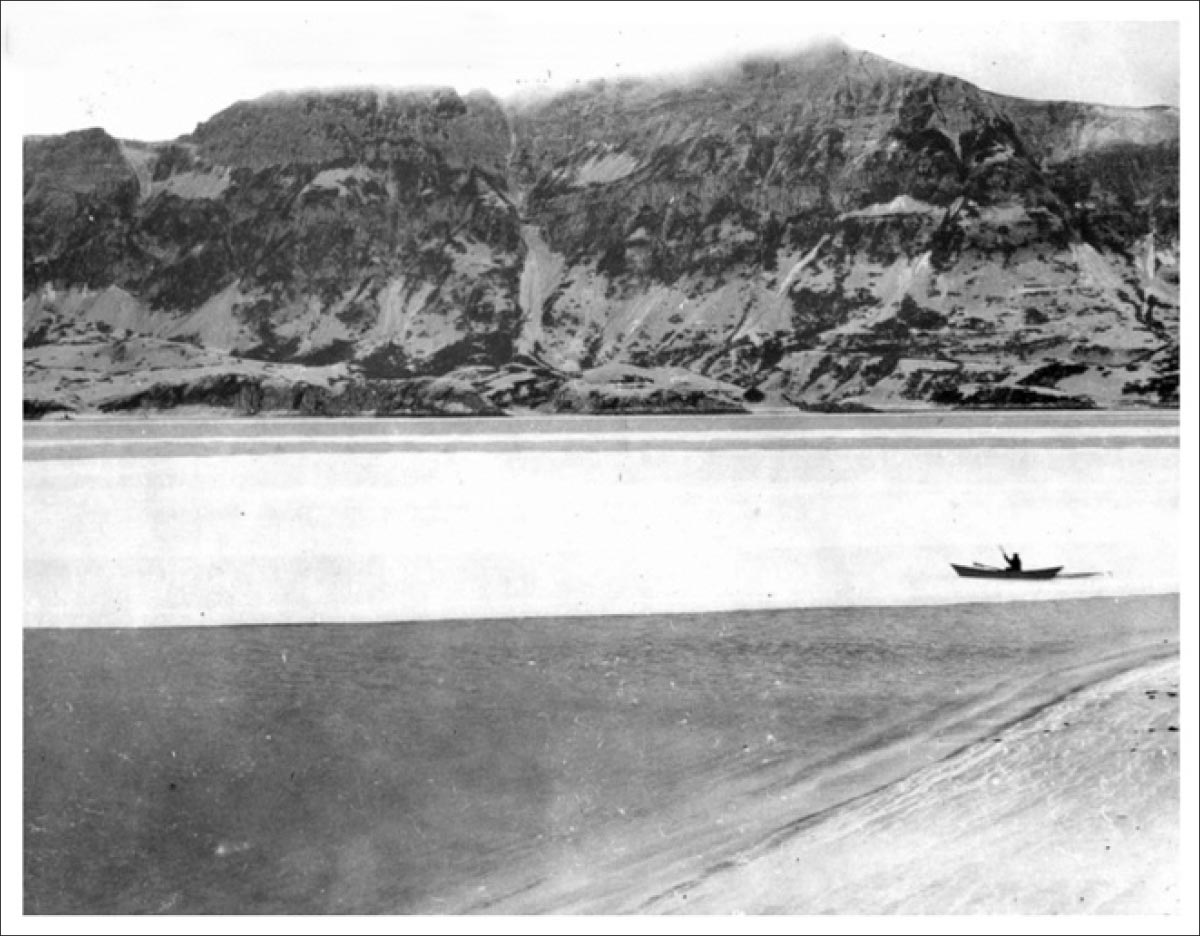

Nasquluq is the Alutiiq word for bull kelp. It comes from the word head. The bull kelp in Alutiiq territory, from Prince William Sound into Cook Inlet and around the Kodiak Archipelago is robust and healthy and has been used for centuries as navigational aid, indicating rocky outcrops and shallower waters, as fishing line made from the long, singular stipe, and as fertilizer, creating soil for potato beds in the post-contact coastal villages of Native and Russian-descended peoples. Generally, seaweeds in Alaska are large and leafy, supercharged by the cold waters. In SW Alaska, there is holey Agarum, golden Alaria, and cabbage-like Costaria, making a three-dimensional tapestry of textures, creating habitat and food source for countless organisms. The 1913 kelp surveys of Western Alaska list Eualaria fistulosa, or dragon kelp as it is called locally, averaging 40 feet long. Dim photographs show blades that would fill entire rooms in length and width. Giant kelp, or Macrocystis pyrifera, is working its way into the kelp play group, becoming more common in the fjords and bays of Kodiak and Afognak with every passing season. Kodiak is the terminus of the giant kelp’s range (although the 1913 report claims it did not exist north of Sitka Sound at that time), but bull kelp, while arriving at the surface later in the year than farther south, makes up the historic kelp beds and extends westward to Umnak Island almost at the bottom of the upfacing crescent of the Aleutian chain of islands.