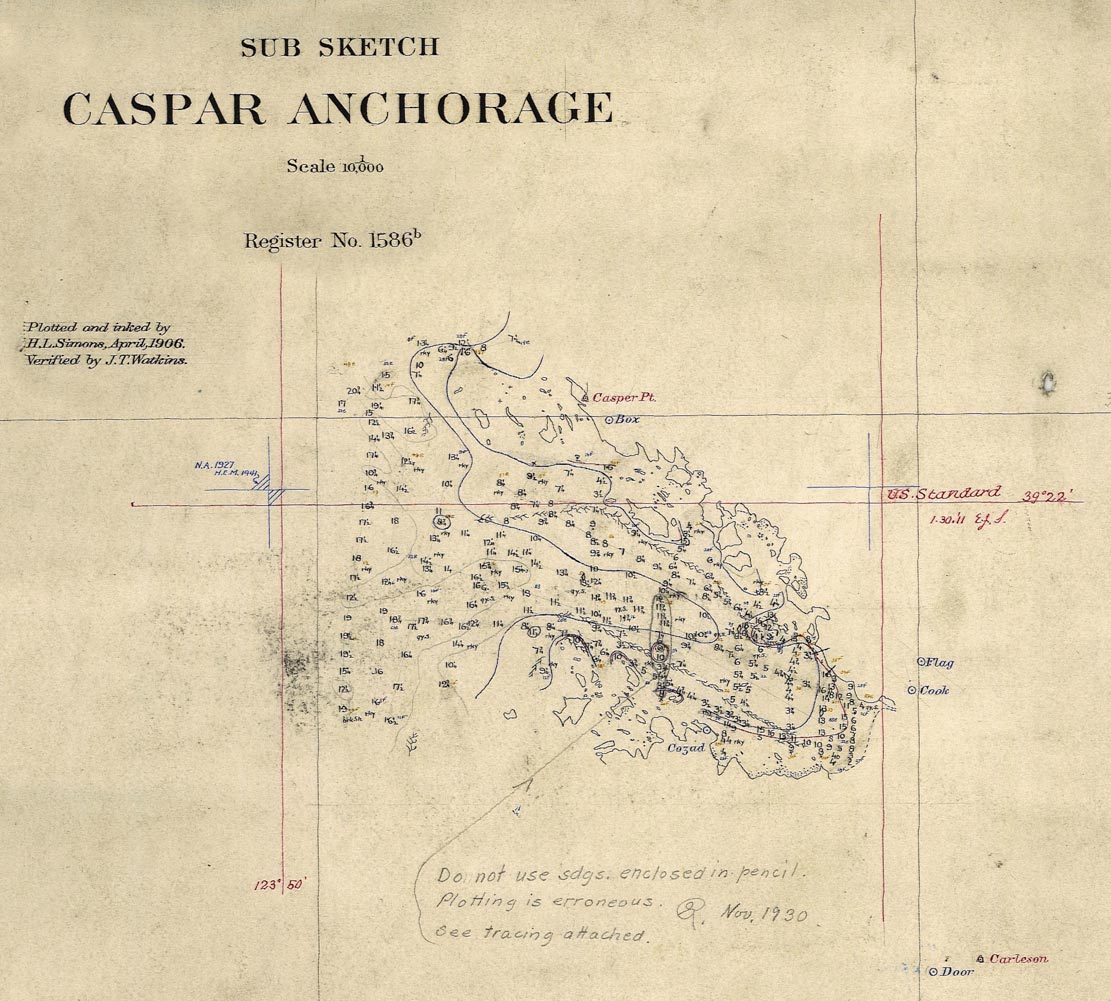

Kelp has been designated by a hand drawn squiggle on nautical charts since these surveys were first produced in the late 1800s for sailing up and down the rocky, fog-shrouded west coast of the North American continent. The canopy forming kelp beds were a navigational landmark, usually indicating a rocky bottom or unseen reefs. In the Strait of Georgia and Johnstone Strait on the eastern side of Vancouver Island, the bull kelp beds could be impassable by sailing ships. On an 1880s nautical chart of the Mendocino County coastline in California, the continuous kelp squiggle of the historic kelp bed there is the outstanding feature. These squiggles have been carried forward in time and are found on contemporary nautical charts created by NOAA for US waters and the Canadian Hydrographic Service (CHS) for Canadian waters. Interestingly, kelp squiggles are not found on charts of waters along the eastern seaboard. The native kelps of the Atlantic do not reach the surface, as bull kelp and giant kelp do, and thus don’t effect maritime navigation along that coast. The collage above represents the joy of discovery when encountering the kelp squiggle on historical charts, pulled up from deep in NOAA’s map archives, but yet the unreliable nature of what maps will tell us about kelp, a habitat-forming organism that is ever-changing and remains mysterious and enigmatic.

Kelp Maps

This is the site of current kelp restoration efforts. The kelp is designated by squiggles along the north and south shore of the cove.

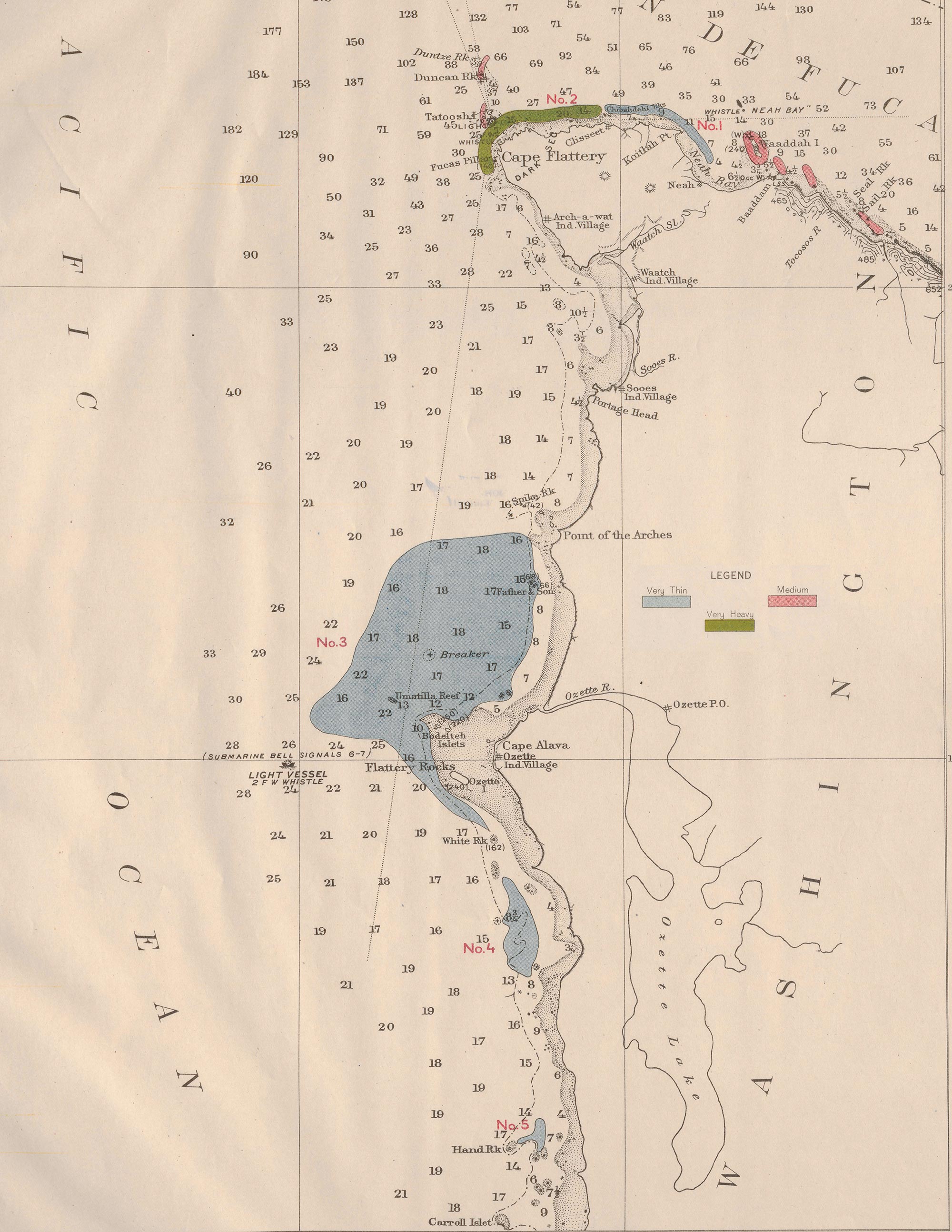

Washington Coast at Cape Flattery, US Dept. of Agriculture, Bureau of Soils, fertilizer investigations, Frank Cameron, in charge. Mapped by W. C. Crandall.

In 1911, The US Department of Agriculture commissioned surveys of all the kelp beds along the entire Pacific Coast of the United States including Alaska. Kelp and seaweed have been used to amend soils around the globe, possibly since agriculture began, and it was hoped to be the source of potassium for the growing fertilizer industry in the US. In 1911 and 1912, steam powered boats with small dories plied our west coast, numbering and measuring every kelp bed and labeling then as either N (Nereocystis) or M ( Macrocystis) or M&N (both). These maps are beautiful and housed at the University of Chicago. When synthetically compounded fertilizer became feasible the interest in kelp disappeared.

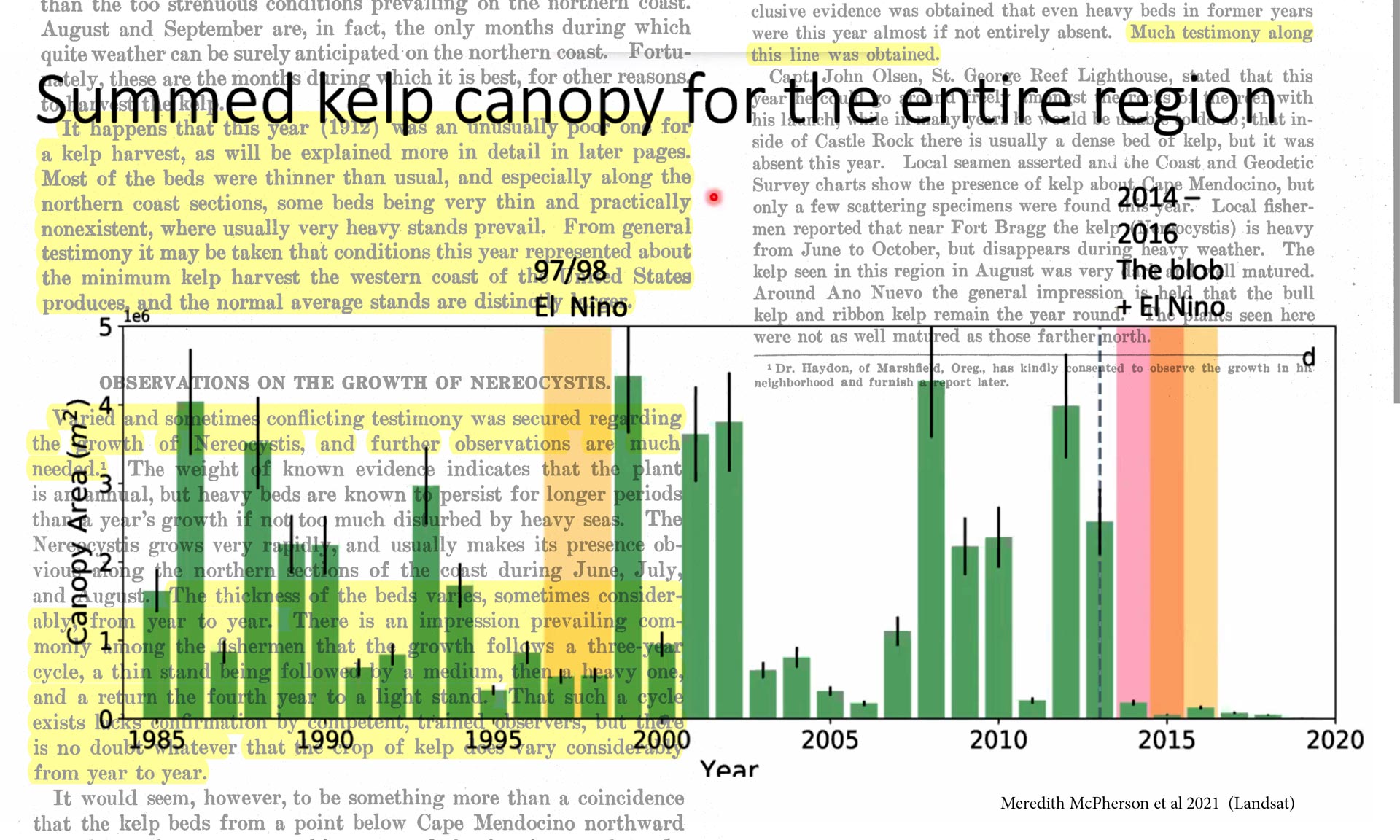

Composite image made by Josie Iselin: graph from Meredith McPherson’s 2021 paper showing kelp abundance of the Sonoma and Mendocino Coast of California overlaid onto the narrative accompanying the 1912 kelp surveys.

Perhaps the most important aspect of the 1911/1912 kelp survey maps is the information the surveyors picked up from local fishermen and lighthouse keepers, as they completed their task: These years (1911–1912) were very lean years for kelp in many places, at the bottom of bull kelp’s 3–4 year cycles of abundance. This narrative is highlighted behind Meredith McPherson’s 2021 graph of kelp abundance on the Northern California Coast showing these cycles, as well as the severe decline after the 2014–2015 warm ocean events. This illustrates how fickle maps—a symbol of endurance—can be when trying to gauge an ephemeral organism like bull kelp.

What is a Shifting Baseline?

A shifting baseline refers to our constantly comparing the now to a past that has changed from the past before that. We normalize a lower level of biodiversity and call it “normal” or “wild.”

There are many current efforts to map the bull kelp beds from California to British Columbia to Alaska, using a range of tools from drones for high-res local kelp bed mapping, to satellites for larger scale canopy kelp mapping, as well as kayakers physically measuring the kelp beds like the surveyors of 1911. They are recording bull kelp at a particular moment, so that comparisons can be made as systems change. Kelpwatch is parsing satellite data from 1984 through 2023, and slowly growing the range of its kelp maps as a time series. But it is important to know how to read the data, comparing the same quarter from year to year and understanding how variable bull kelp is from season to season and from year to year. Kelp mapping resources are being produced by working groups all across bull kelp’s range. Our hope and plan is for this page to become a resource for accessing this kelp mapping data and resources.

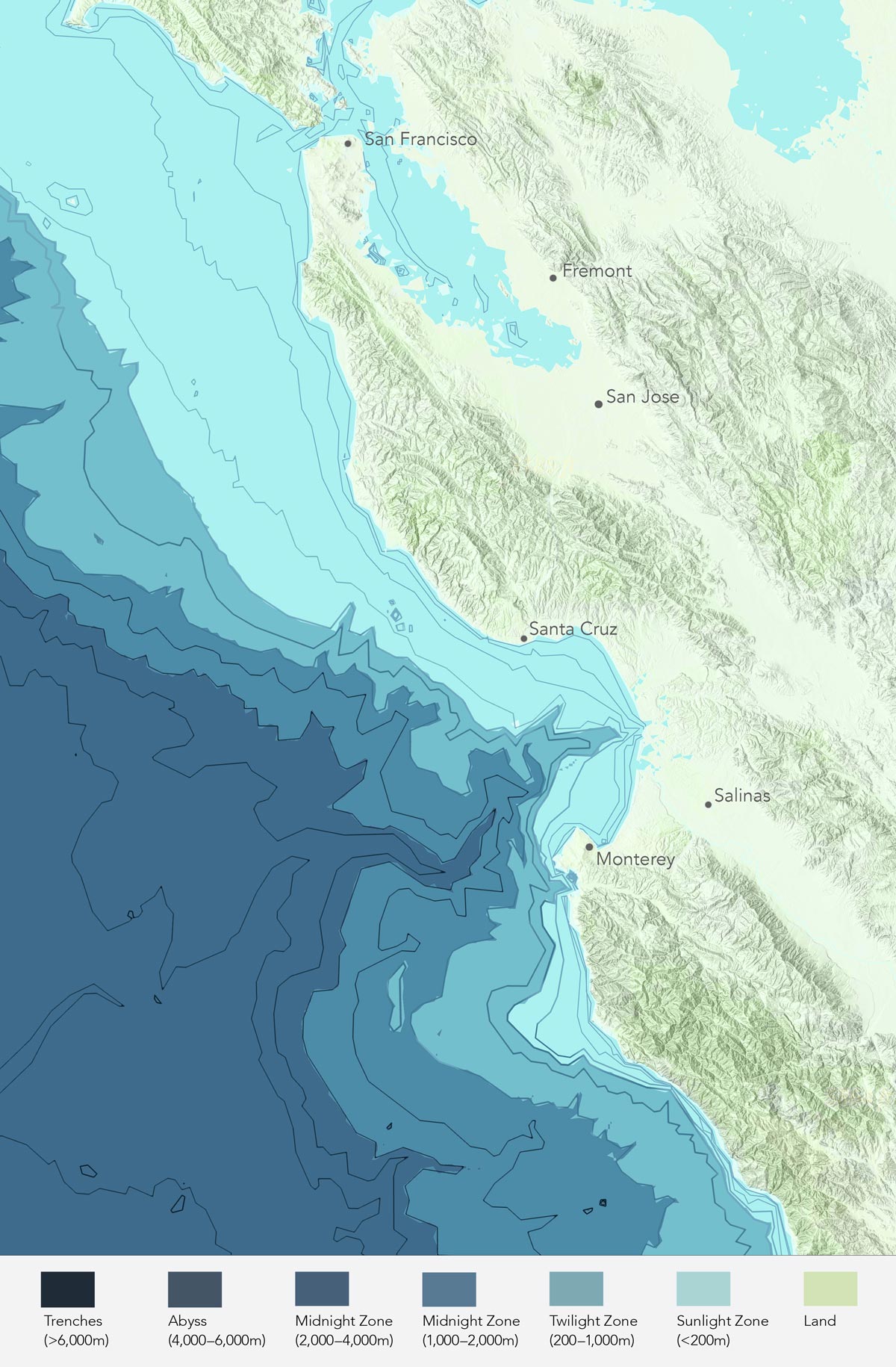

Central California regional map: Sea & Shore Solutions used many source files to generate coastal maps exclusively for this website. Above/Below then refined these to make the final maps used on the regional story pages.

Our terrestrial landscapes are extensively mapped with detailed topographic information available for every inch of forest we might want to hike into. But finding comparable and consistent maps of ocean floor topography, or bathymetry, is a veritable goose-chase. Between private mapping companies and federal agencies, our oceans are represented by a hodgepodge of garish colors and varying looks and detail. To provide a set of maps to orient our readers to each regional bull kelp story, we ended up making our own. With the help of Sea & Shore Solutions, we came up with what we think are beautiful maps with just the right amount of bathymetric information, and that can be used either as image files or with layered GIS data when we wish.

Indigenous peoples have long recognized the reciprocal relationship between humans and the coastal and marine environment during thousands of years of continuous residence. Here are some of the Tribal community networks and collaboratives actively managing coastal areas and kelp restoration in territories adjacent to bull kelp habitat today:

Marine Plan Partnership (MaPP)

Tribal Marine Stewardship Network

InterTribal Sinkyone Wilderness Council

Gwaii Haanas Land-Sea-People Management Plan

We would like to build this list of Tribal ocean networks and collaboratives in future versions of this website. Please let us know if you would like your organization or initiative to be included in this directory.

Marine protected areas (MPAs) are regions defined by federal and state agencies that are designated and managed for the long-term conservation of marine resources, ecosystems services, or cultural heritage.

MPA designations range from no-take reserves to limited and regulated fishing and recreational harvest and uses. These marine habitats and the variety of species that they support are managed by an array of agencies from NOAA’s Federal National Marine Sanctuaries, to state Fish and Wildlife agencies to Tribal networks and collaborations. MPAs are not as well known or appreciated as our national, state, and county parks on land and can have different names — including marine parks, marine conservation zones, marine reserves, marine sanctuaries, and no-take zones. While there are differing perspectives on MPAs, they are intended to provide long term protection to important marine and coastal ecosystems that yield a wide range of benefits, including biodiversity conservation, coastal protection, food and livelihoods for local communities, and carbon storage. Data collection on the effectiveness of MPAs is ongoing but there is indication that increased fish populations spillover into nearby waters, benefiting fishing in the non-regulated neighboring waters. The 30x30 initiative, combined with Indigenous Marine Stewardship Areas (IMSA), aims to protect 30% of the oceans by 2030 through strategies that include marine protected areas.

MPAs can help protect kelp forests by limiting fishing, commercial and recreational harvesting of kelp and abalone, and other human activities that can harm kelp forests. We encourage everyone to get to know the stretch of coast where they live or like to visit, to understand the management and regulations to help protect bull kelp habitat coastwide.

Federally Managed MPAs (in US)

The National Marine Sanctuary System was established in 1972 and manages and protects 14 specially designated areas of the nation’s oceans and Great Lakes for their conservation, recreational, ecological, historical, cultural, archaeological, scientific, educational, or aesthetic qualities. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) oversees this system.

Federally Managed MPAs

Alaska Marine Protected Areas

There are currently 11 Marine Protected Areas managed by various federal agencies in Alaska which include a National Wildlife Refuge as well a Habitat Conservation Areas, Habitat Conservation Zones and Habitat Protection Areas.

British Columbia

Marine protected areas are well established in Pacific Canada. British Columbia’s first protected area with a marine component was designated in 1911, and there are now over 185 MPAs protecting 28 percent of BC’s coastline and 2.8 percent of Pacific Canada’s Exclusive Economic Zone. Some of Canadian MPAs are jointly managed with First Nations of the area.

Washington

Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary OCNMS was established in 1994 and includes 3,188 square miles of marine waters off the rugged Olympic Peninsula in northwest Washington state. The sanctuary covers much of the continental shelf and several major submarine canyons, with upwelling that supports locally abundant marine life and supports seasonal populations of marine mammals and seabirds. Along its shores are thriving kelp and intertidal communities, teeming with fishes and other sea life.

Northern California

Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary: Located off the Central California coast and encompassing 966 square nautical miles, Gulf of the Farallones National Marine Sanctuary protects a diversity of highly productive marine habitats and supports an abundance of species. It is a complex system of bays, estuaries, mudflats, marsh and intertidal, coastal and oceanic waters, and is influenced by the highly urbanized San Francisco Bay area populated by nearly 8 million people. The sanctuary has one of the world’s most significant populations of white sharks, in addition to one of the largest concentrations of breeding seabirds.

Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuary (CBNMS) was designated in 1989 and expanded to its current size of 1,286 square miles in 2015. The sanctuary is entirely offshore, with its southern boundary located 42 miles north of San Francisco, eastern boundary located six miles from shore, and western boundary located 30 miles from shore. Seafloor features, such as the rocky Cordell Bank, deep Bodega Canyon, steep slope, and continental shelf habitats, combined with significant upwelling ocean conditions, create an extremely productive marine environment in CBNMS, with an array of species that contribute to the sanctuary’s unique biodiversity.

Central California

Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary: Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary is the second largest national marine sanctuary and the largest marine protected area in the continental United States. Within the boundaries of the sanctuary is a rich array of habitats from rugged rocky shores and lush kelp forests to one of the largest underwater canyons in North America. These habitats abound with life, from tiny microscopic plants to enormous blue whales. The sanctuary is home to a diversity of species including marine mammals, seabirds and shorebirds, sea turtles, fishes, invertebrates, and marine algae.

Chumash National Marine Sanctuary: For more than 40 years, local community members and elected leaders along California’s Central Coast have advocated for the establishment of a national marine sanctuary. In 2013, the Northern Chumash Tribal Council launched a campaign to secure formal sanctuary designation. The nomination was accepted by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) two years later and placed on an official list for future consideration.

State Managed MPAs

Alaska

State protected marine areas are managed by the Alaska Department of Natural Resources and includes 33 State Marine Parks, a Marine Reserve and a State Recreation Area.

British Columbia

Working together, many First Nations, the Province of British Columbia, and the Government of Canada have developed a plan for a Marine Protected Area Network in the Northern Shelf Bioregion, which extends from the top of Vancouver Island (Quadra Island / Bute Inlet) and reaches north to the Canada-Alaska border.

Washington Coast & Puget Sound

The state marine protected areas in Washington State, including on the coast as well as throughout Puget Sound, are managed by the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife and include 9 Marine Conservation Areas, 17 Marine Preserves and 6 Sea Urchin and Sea Cucumber Exclusion Zones.

Northwest Straits

Since 1998, the Northwest Straits Initiative has worked as a community-led collaboration to protect and restore the marine environment of northwest Washington State. The Initiative includes seven county-based Marine Resources Committees (MRCs) that are made up of volunteers representing diverse perspectives in their communities.

Oregon

In 2012, Oregon completed the planning and designation of five marine reserve sites. The Cape Falcon, Cascade Head, Otter Rock, Cape Perpetua, and Redfish Rocks sites are each named after local natural landmarks. Oregon’s five marine reserve sites are areas in the ocean dedicated to conservation and scientific research. These sites are managed as a system by the State of Oregon, with the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW) as the lead management and monitoring agency. The Marine Reserves Program Synthesis Report provides a comprehensive overview of the ODFW Marine Reserves Program and the initial implementation of Oregon’s five marine reserve sites, from 2009–2021.

California

In California, there are 124 MPAs spanning 1110 miles from Mexico to the Oregon border (crossing 14 coastal counties), protecting 16% of state waters. This statewide network of MPAs was established in 2012 and is the country’s largest. The recently completed Decadal Management Review represents the first ever comprehensive evaluation of the entire statewide MPA Network. These MPAs are managed by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW).