Redwoods of the Ocean

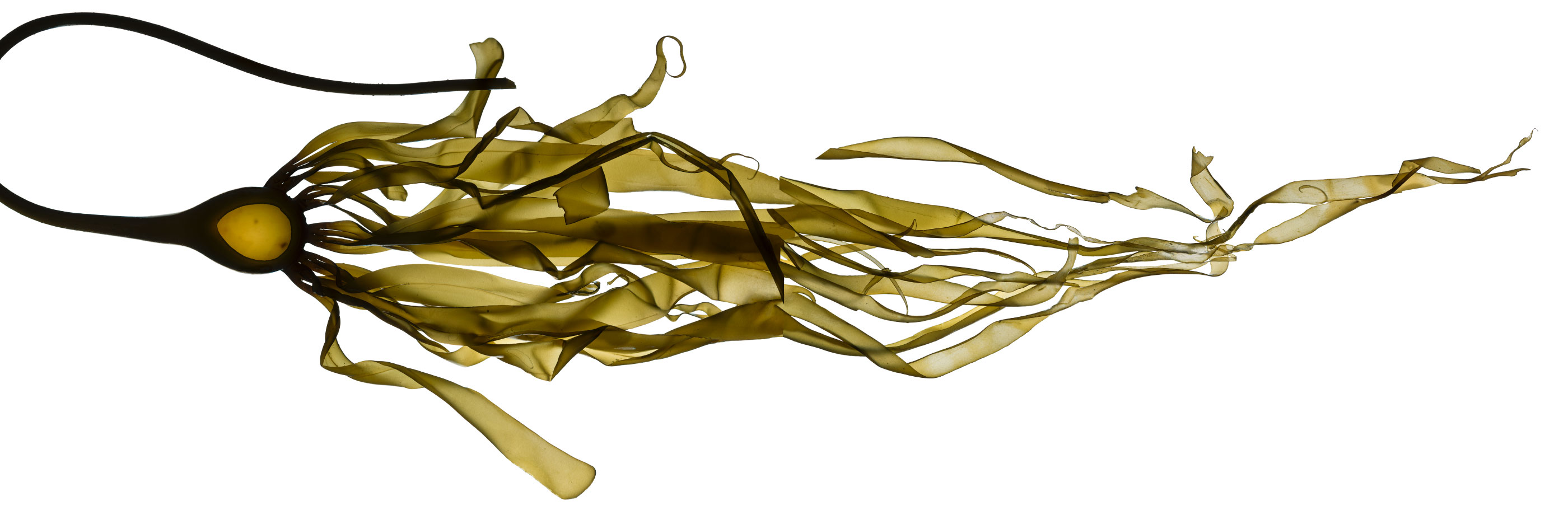

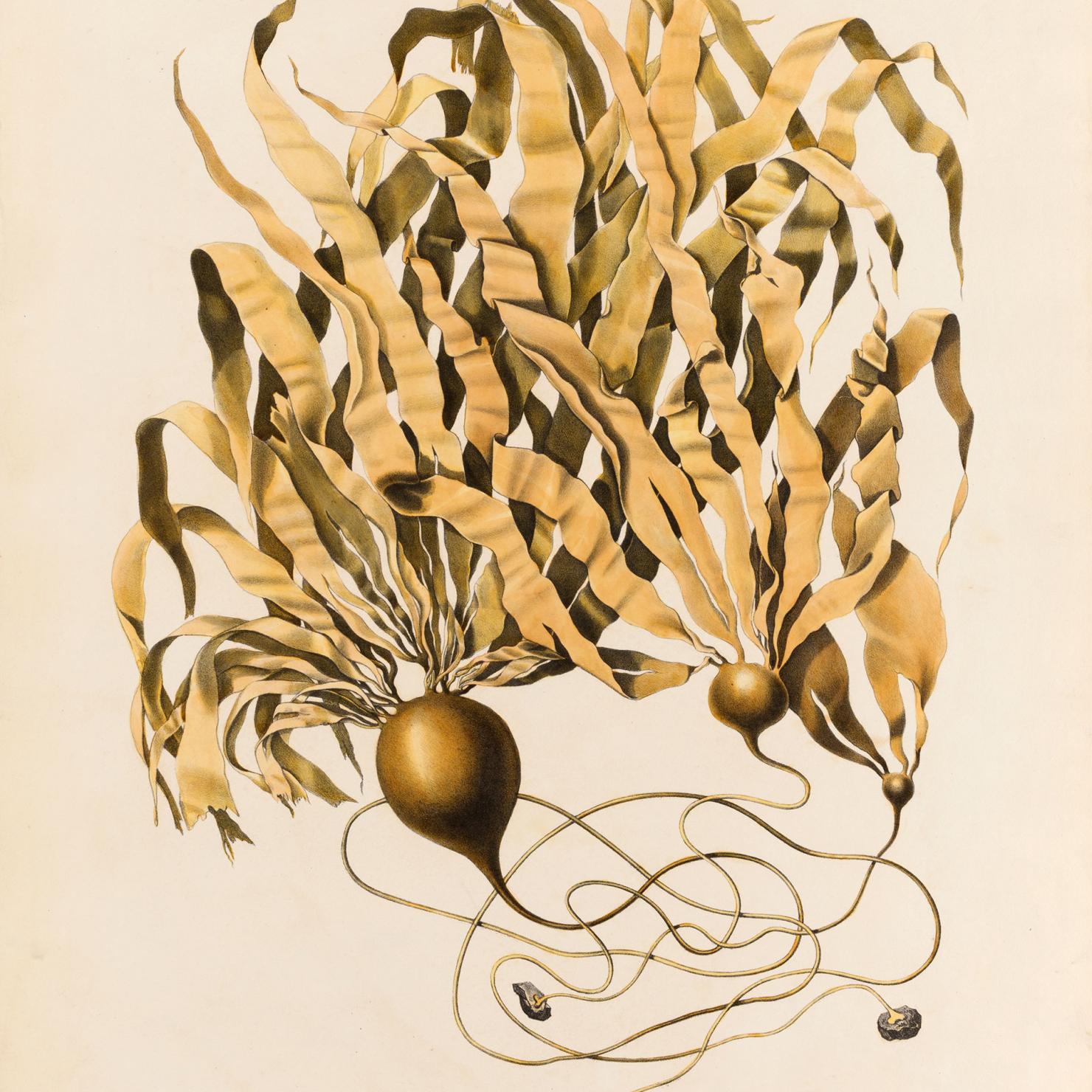

Bull Kelp (Nereocystis luetkeana) is the majestic kelp that grows up to sixty feet in one season, to reproduce and be washed away by winter storms each year. It is the signature species making up the vastly productive kelp forests of the Northern Pacific coastline from Central California through Northern California, the Pacific Northwest, British Columbia, Alaska, and halfway through the Aleutian Islands. It is the kelp within which herring school and spawn, rockfish abound, seals seek prey and refuge from sharks, and young salmon adapt to their salty home. It is the canopy under which countless other seaweeds grow including the understory kelps and pink rock-encrusting coralline algae that attract the settling of urchin and abalone and young bull kelp. Under the gestural swaying largess of the bull kelp is a colorful world with sea stars and nudibranchs and sponges. There are other large kelps in the mix—Macrocystis pyrifera, or giant kelp, dominates the kelp forests south of Monterey clear to Mexico, and understory kelps such as feather boa kelp and bladder-chain wrack will be found washing ashore—but from Central California to Alaska, bull kelp is the major player, massive and hefty, thriving in the nutrient-rich, cold waters of the Northern Pacific.

What is The Bull Kelp Forest?

Bull kelp is the algal species that creates the rich, underwater ecosystem where hundreds of species thrive. These ocean forests are as diverse and abundant and important for life on earth as any of our terrestrial forests. Bull kelp grows just a few hundred yards from shore in what is known as the subtidal zone, needing a rocky bottom to hold onto and enough sunlight to promote growth. The continual sloughing away of the bull kelp blades creates a snowstorm of organic matter (known as detritus) that feeds countless organisms, such as shrimp, isopods, snails, crabs, urchin, and abalone. These low-level detritivores are important food sources for herring, rockfish, juvenile salmon, lingcod and then these in turn build the food web important for marine birds and mammals such as seals, sea otter, murres, pelicans, and even whales. Bull kelp detritus thrown onto the beach, known as wrack, is decomposed by kelp flies and amphipods, which are an important protein source for shorebirds. The web of interdependencies is known as the trophic food web (who eats whom), and the majestic bull kelp is the underpinning of all this complexity in the coastal waters of the Northeastern Pacific Ocean.