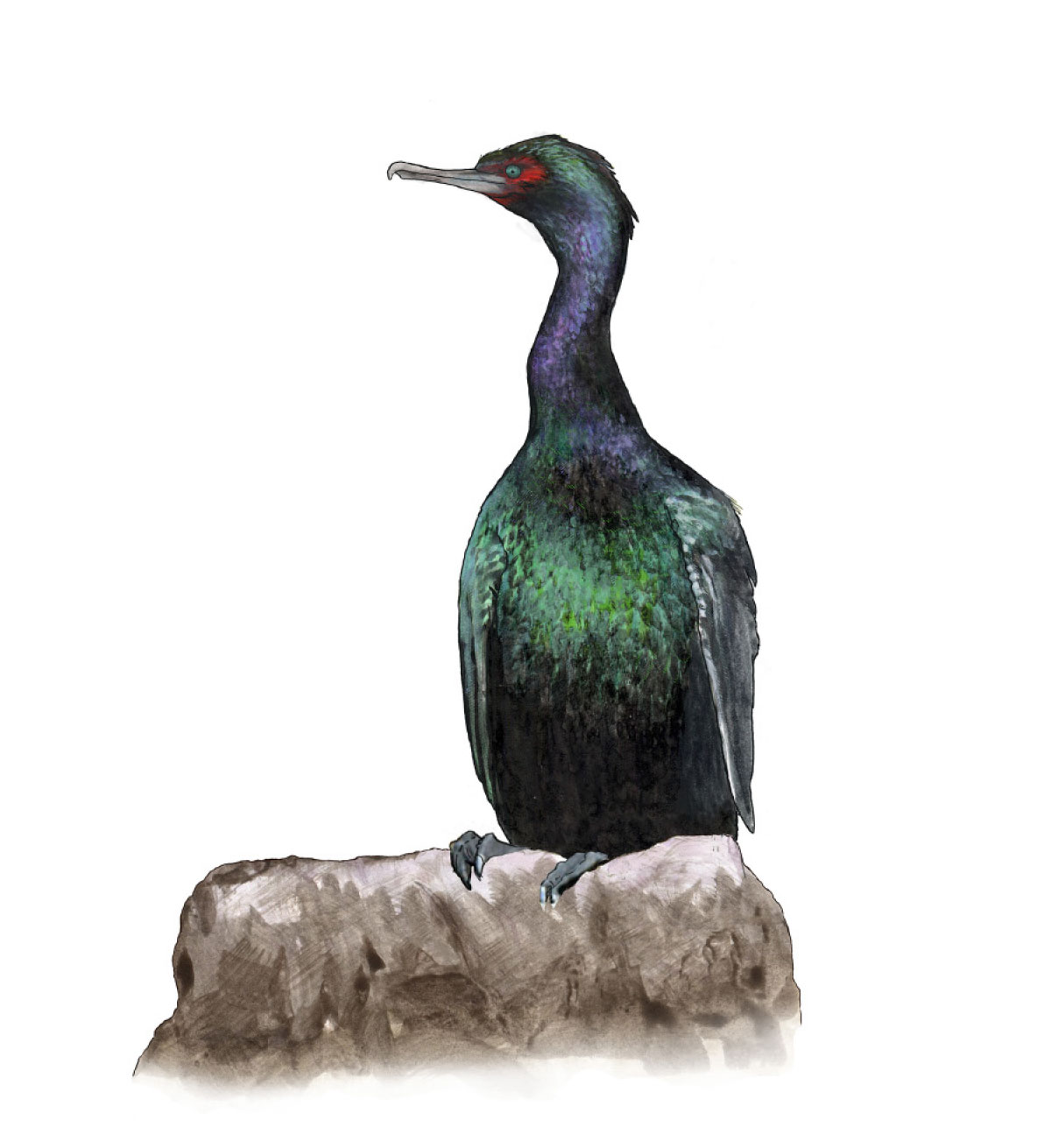

The Pelagic Cormorant also benefits directly from the bull kelp forest, but as an oceanic, fish-eating bird, the kelp’s benefit to the cormorant is as ecosystem engineer. The bull kelp forest is home to anchovies, herring, and up to thirty different kinds of young and forage fish the cormorants are so good at diving to catch and eat. Despite its name referencing the open ocean, the pelagic cormorant hugs the shores of the North Pacific, rarely flying farther from the coast than the rocky, kelp forest zone. Cormorants are spectacular divers, becoming black torpedoes underwater, and can hold their breath for up to two minutes, preying on fish within the bull kelp forest. They overlap with pigeon guillemots in range and species of prey, but pelagic cormorants eat the larger fish while the guillemots eat the smaller ones. Even the three species of cormorant found along the Pacific Coast—pelagic, Brandts, and double-crested—all have subtle differences in their forage zones so as not to compete with each other. They also nest in different ways. The pelagic cormorants nest on small slivers of shelf on cliff faces facing the ocean, laying eggs and growing young in what seems like impossible circumstances. By late July/early August, each nest might have two or three young cormorants, as big as their parents but identified by their lackluster feathers that are not yet shiny. Their speedy growth, from fuzzy chick to full-sized cormorant in two months—like the nearby gull and common murre young as well—is a testament to the nutrient riches offshore that drive such growth. The subsidies of the bull kelp forest to this seabird lifecycle are tied directly to its status as a habitat-creator for the fish that it depends upon to survive.

Cormorants also use kelp wrack to build their nests along coastal cliffs, using their guano to stick the kelp and seaweed fronds together and in turn glued to the steep rocks, adding stability to the precarious positioning. Cormorants stealing their fresh seaweed collections from each other is not an uncommon sighting. The year-round range of the pelagic cormorant closely mimics the range of bull kelp itself, suggesting a close connection between the kelp forest below the surface and these fantastic fishers who dive into it.