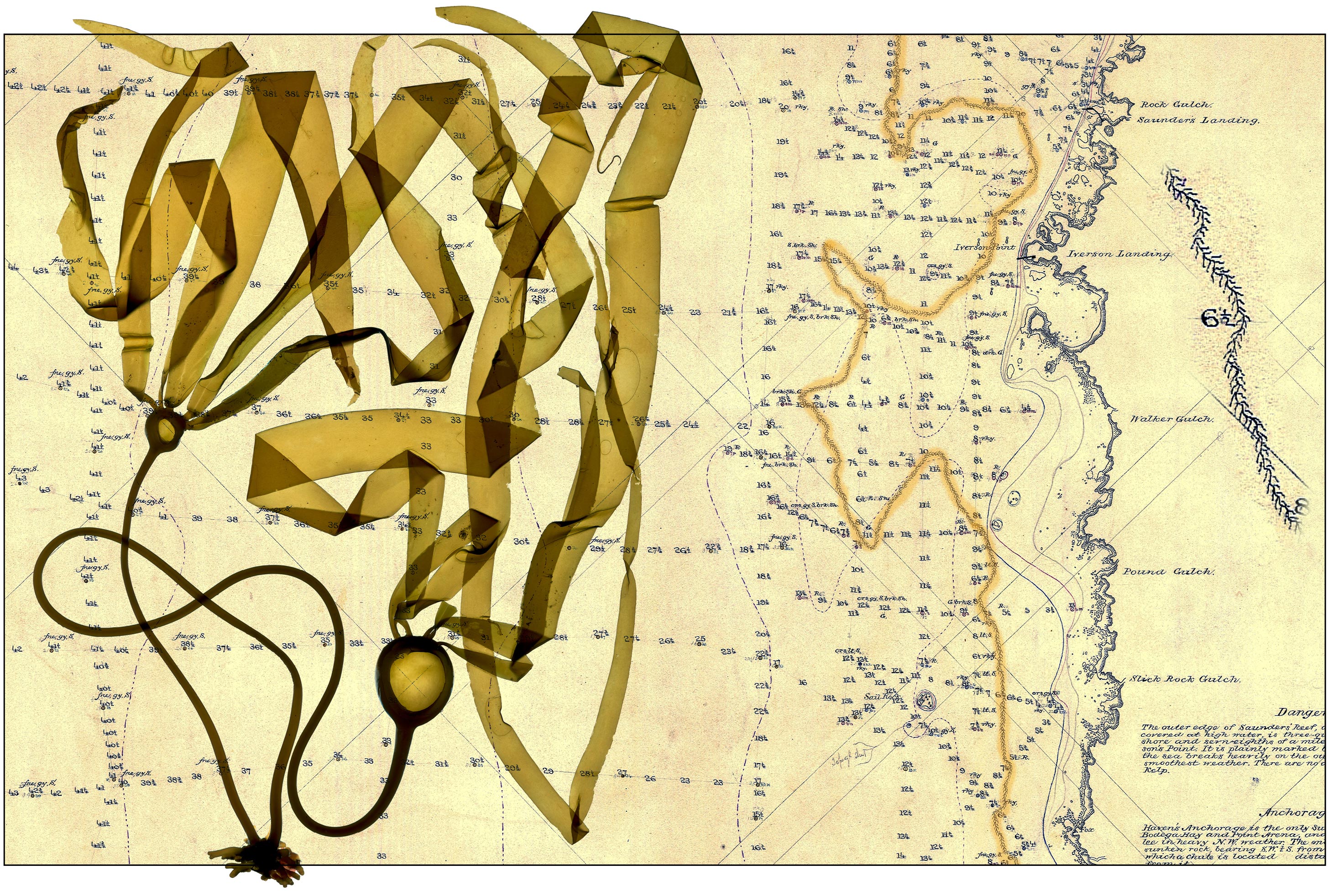

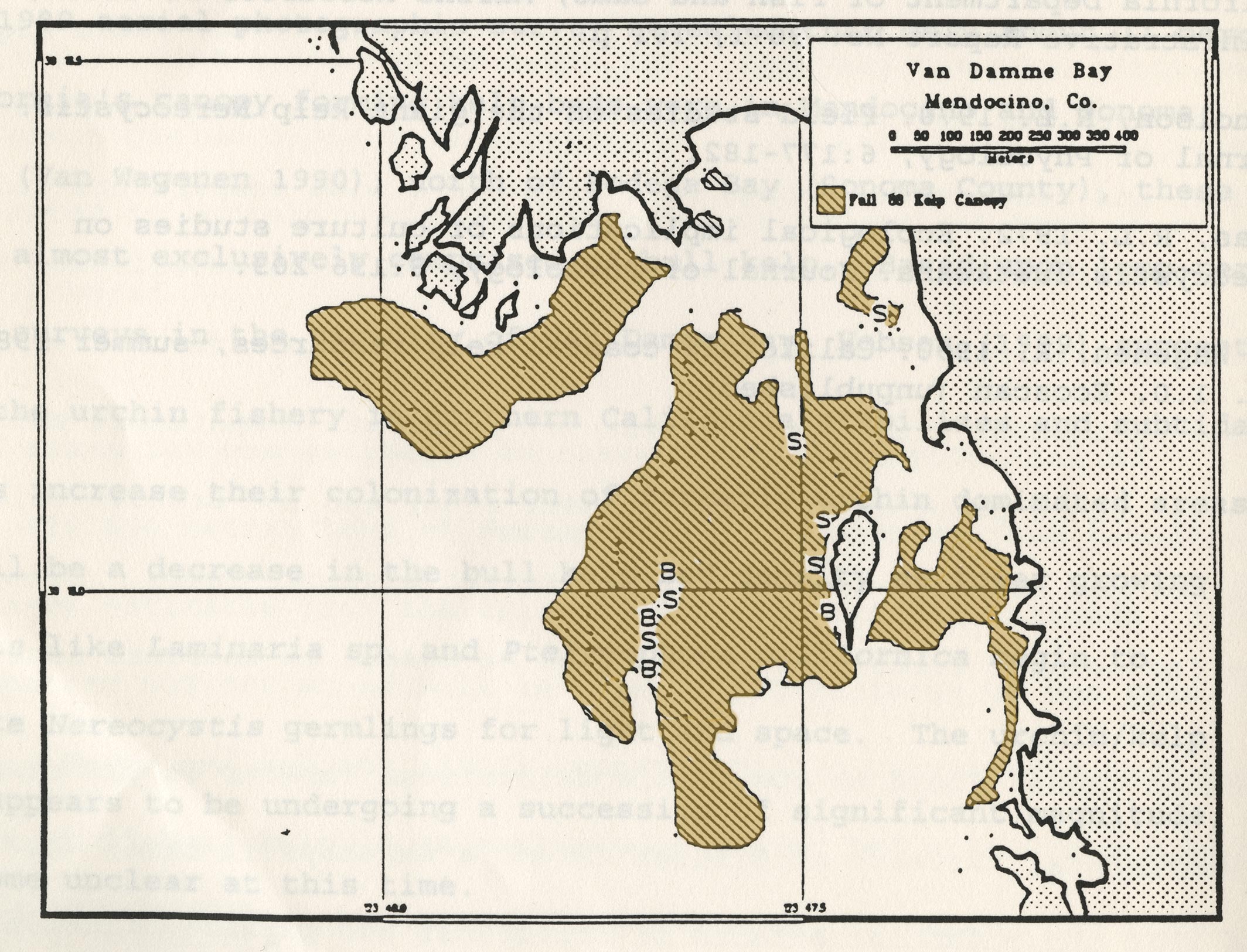

The yellowed, hand-drawn 1880s nautical survey for the stretch of Pacific waters that covers the southern section of Mendocino county coastline has one outstanding feature: a thick curving line stretching from the top of the navigational map to the bottom indicating an unbroken kelp bed along this coast (see below). On close inspection this curving line is made up of thousands of small inked squiggles. The line of squiggles hitches ocean-ward in a squared off protrusion at one of the few points on the coastline that has a name: Saunders Landing. The line of squiggles indicates the bull kelp that thrived in the cold, rough waters off the coast of Sonoma and Mendocino counties before they were even counties. That hitch is the bull kelp of Saunders Reef, a persistent kelp bed whose glistening tubular kelp we can see today from the pullout on Route 1. These magnificent organisms might be direct descendants of the bull kelp of the 1800s.

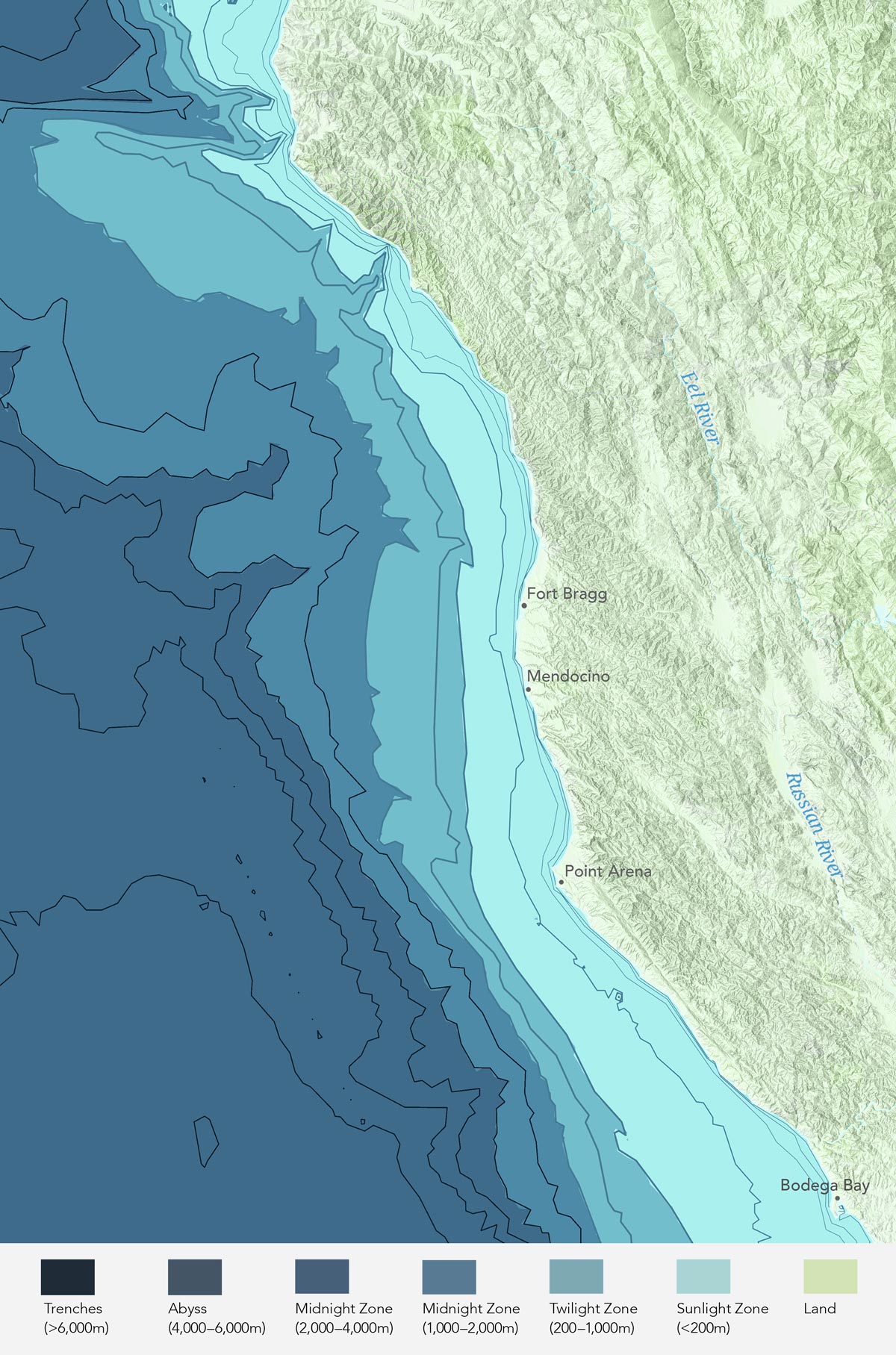

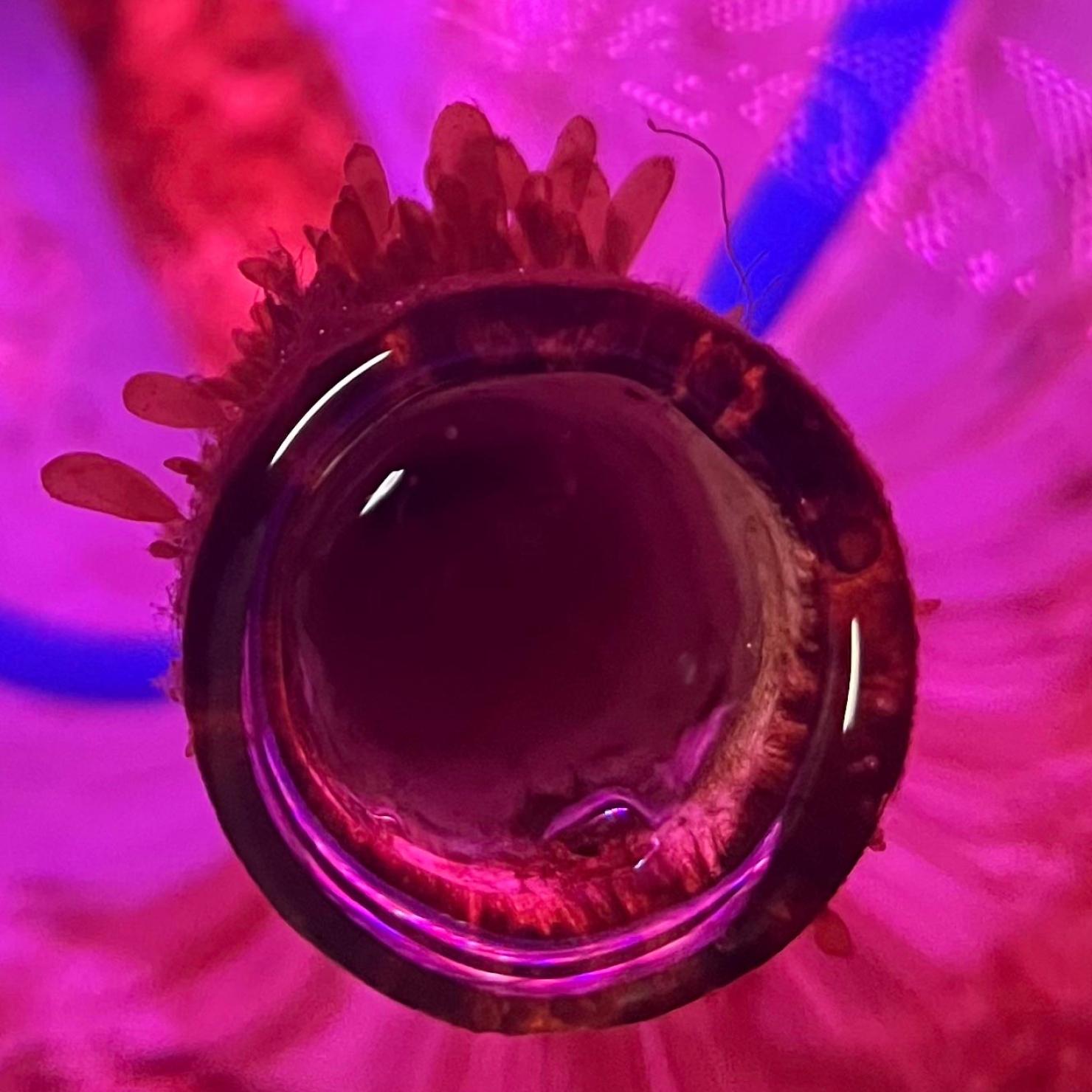

Looking out at Saunders Reef, 15-foot waves break one hundred yards out and push massive volumes of water in amongst the fragments of the continent, the chimneys and rock outcroppings that stand up along the rugged coastline. The kelp and seaweed ecosystems need to be rejuvenated by the energy and dynamics of winter storm systems, spring winds and seasonal upwelling—the conveyor belt of feedstock for the planktonic and algal base of the food chain. This upwelling of nutrients provides the resources the bull kelp need for its prodigious spring-time growth, from a tiny, fragile leaflet at the ocean bottom in March, to the massive sixty-foot stipe and bladder streaming up to 60 magnificent blades by July. In turn this churning ocean and kelp forest supports the sea birds wheeling overhead, the flash of a seal thrashing salmon in the surf, migrating whales, other fish species and so much more.