Tatoosh Island is a hiccup off the pointy nose of the Olympic Peninsula that is Cape Flattery. Tatoosh is a tiny island with enormous importance to the Makah, the Cape People, as a whaling station and central to their territory and lifeways along this section of the coast of Washington State—an amalgam of pounding surf, high, spiked sea stacks, and sandy beaches in between. The land turns a sharp corner here tracing the edge of the dynamic, open Pacific Ocean into the quieter Strait of Juan de Fuca. The bull kelp beds along this section of coastline, both facing the open Pacific and into the Strait, are historic, and robust and healthy. They offer us humans plentiful lessons to learn from.

Washington Coast

“I want the sea. That is my country.”

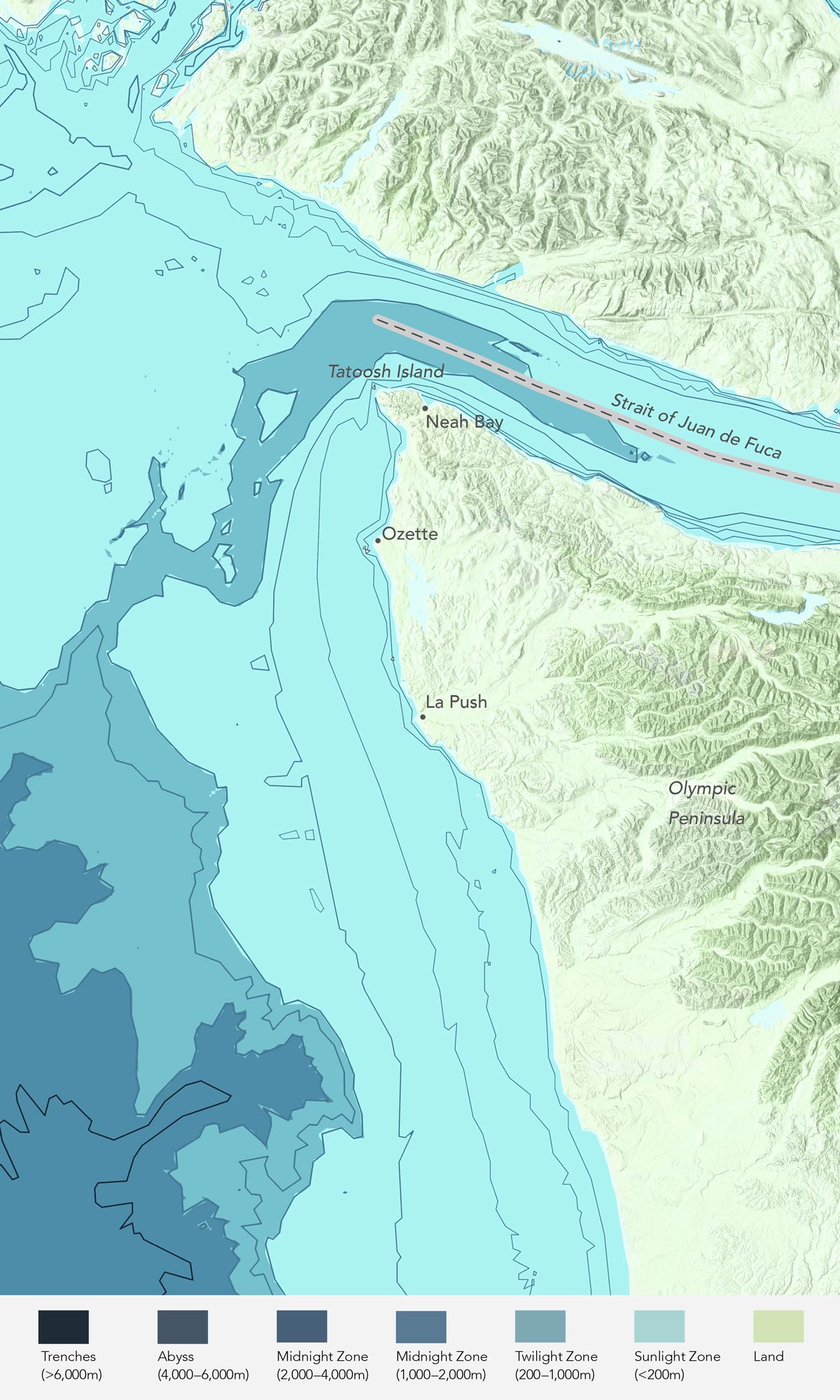

Outer coast of the Olympic Peninsula, Washington, from La Push to Tatoosh Island off of Cape Flattery and into the Strait of Juan de Fuca past Neah Bay.

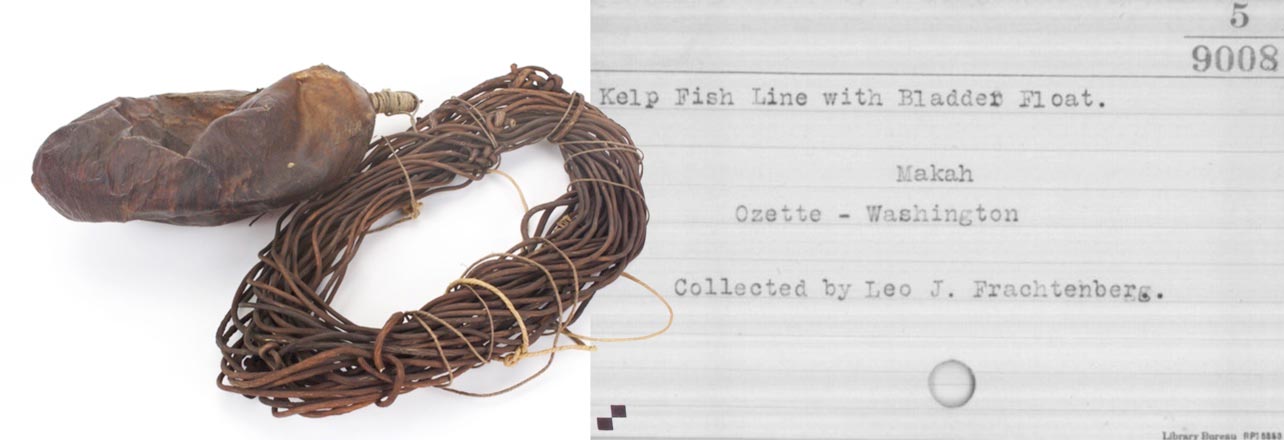

Makah Fishing Line Made From Bull Kelp

This kelp fishing line, from the collection of the Smithsonian Museum of the American Indian, was collected at the coastal village of Ozette in 1916. The unique ability of bull kelp to grow a long (easily 45–60 feet long), thin, uniformly-cylindrical, stipe provides material for fishing lines of durability and effectiveness. Tribes throughout the Pacific Northwest and into Alaska would treat and tie together bull kelp stipes for use as fishing lines. The one pictured here is from the Makah whaling village at Ozette, on the outer coast of the Olympic Peninsula, where plenty of bull kelp would wash up on the beach with long, golden stipes, a beneficence to the Makah fishers, or perhaps it was harvested fresh from the kelp beds just offshore. In 1920 all of Ozette’s residents moved to Neah Bay; the federal government was requiring their children to attend school and none was provided at the village.

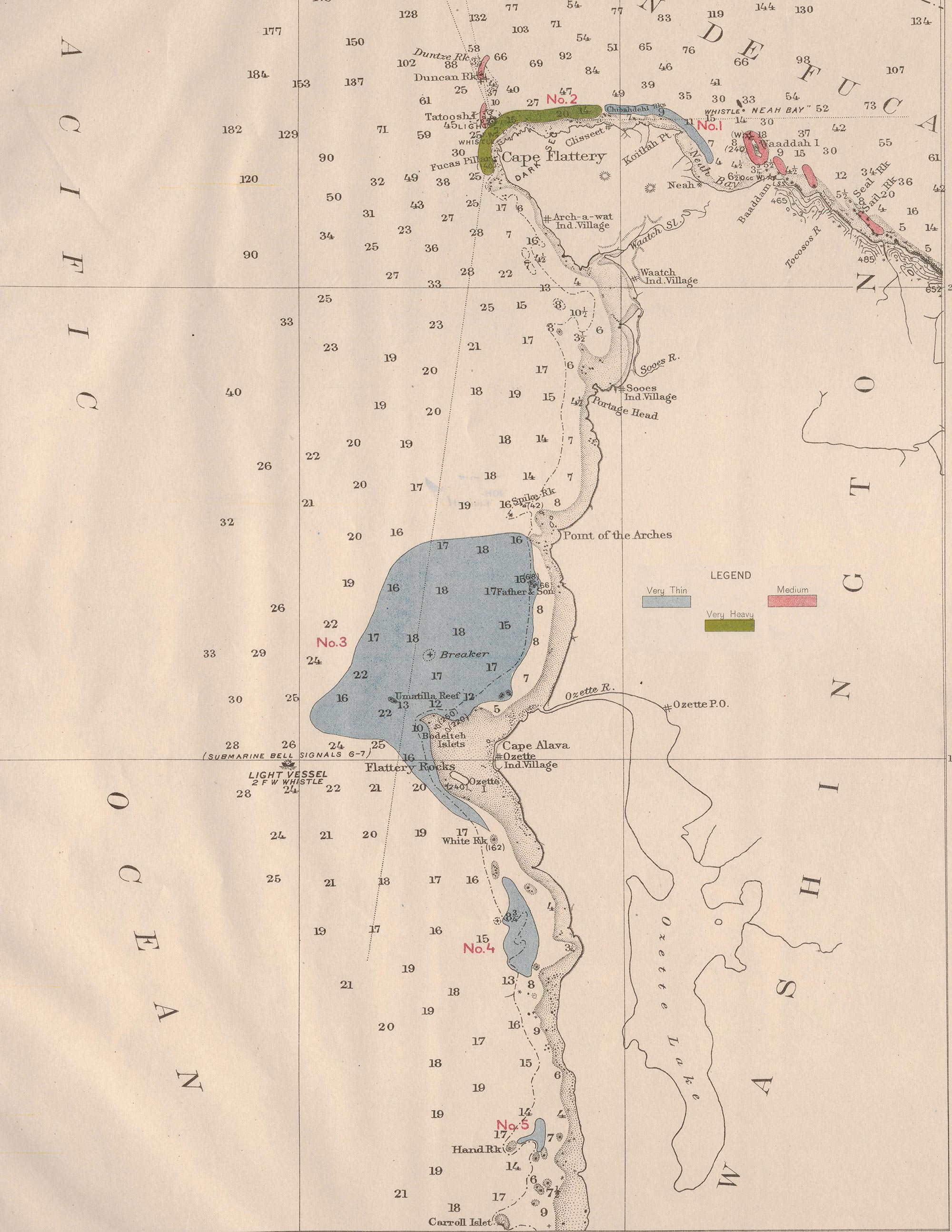

1912 kelp bed survey map of the Washington Coast by the US Dept. of Agriculture. The outer coast surveys were done by W. C. Crandall and the Puget Sound surveys were done by George B. Rigg.

In partnership with the Makah tribe, Tatoosh Island and the surrounding coastline has been the site of ecological study for decades. Makah Bay and then Tatoosh is where Bob Paine did his famous sea star experiments and honed his ideas that resulted in the first use of the term “keystone species.” Cathy Pfister and University of Chicago researchers have studied the abundant kelp beds surrounding the island for many years, and aerial surveys by the Washington Department of Natural Resources started in 1989 and continue to track the dynamics of kelp canopy in this region.

One of the most interesting things about the kelp beds along this section of coast–at Cape Alava, and then as it turns a 120 degree corner at Tatoosh Island, and other beds at Koitlah Point and Bullman Beach past Neah Bay–is the long-term intertwined connection between the kelp cousins, Nereocystis and Macrocystis. Geographically, Nereo and Macro grow together in a variety of relationships given where you are. Here they are combined beds as in Carmel Bay just below the Monterey Peninsula. On the Northern California Coast, bull kelp dominates historically with very little giant kelp presence to speak of, and in SE Alaska the bull kelp beds and giant kelps beds are distinct, being in different locations. At Kodiak Island in Southwest Alaska, giant kelp is just coming into the mix and it will be interesting to see how the two cousins relate there going forward. In the 1912 kelp surveys of the Washington Coast, Bed #4 is at South White Rock just off Cape Alava. It is indicated as Nereocystis and Macrocystis—a combined bed.

Today, this same kelp bed is still mixed as are the other two mentioned. The thirty-three year data sets show a deep correlation between the Nereocystis and Macrosystis in these areas. Their fates are entwined. When one does well, the other does well. When one declines, the other declines. These two do not constitute a “portfolio” or a reassurance that one will hedge against stressors for the other. They are not in competition, and despite their subtle differences—Macrocystis is a perennial and tends to have more animal communities associated with it, while Nereocystis is an annual—this coherence is a danger in the face of rapidly warming oceans.

Sea Otter and Sunflower Sea Star: Are They Here?

Yes! There are lots of sea otters along the Olympic Peninsula coastline.

There are almost 3,000 of the northern sea otter subspecies (Enhydra lutris kenyoni) ranging from just south of Destruction Island north around Cape Flattery to Pillar Point, half way along the Strait of Juan de Fuca. These otters are descended from 59 individual otters translocated from Amchitka Island in advance of the atomic bomb tests there—29 released at Point Grenville in 1969, and 30 released at La Push in 1970. Many of these original sea otters died but a small group survived to expand their population along this open Pacific coastline with both rocky bottom habitat—ideal for both bull kelp and sea otter forage foods such as urchin and crab—as well as sandy habitat, rich with razor clams, another sea otter favorite.

No. There are very few sunflower sea stars here.

Since the starfish wasting disease emerged in 2014, very few sunfower sea stars have been spotted off Tatoosh Island and the surrounding waters. It is believed that even if juvenile sunflower sea stars were present or were translocated from other vicinities, they would eventually succumb to the wasting disease that seems to still be present in coastal waters.

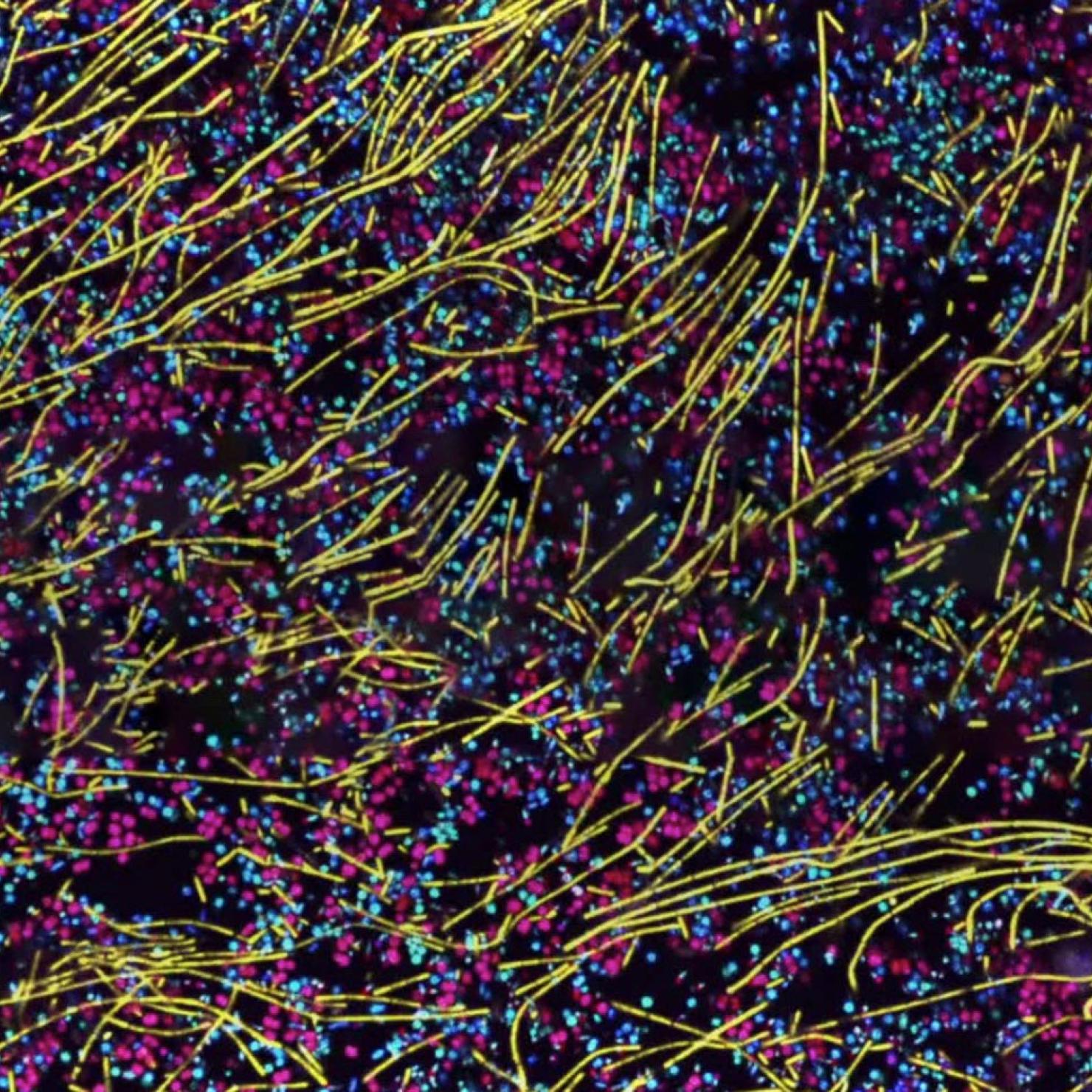

Each color is a different taxonomic group of bacteria.

Scientists at the Marine Biological Lab in Woods Hole, MA (J. Mark Welch and T. Ramirez-Puebla) have revealed dense microbial communities on the blades of bull kelp. The microbiome of the bull kelp, just like the microbiome of our own gut, is essential for its healthy growth. It creates a biofilm on the surface of the kelp which acts as a barrier or repellent to epiphytic growth—those bryozoans and other algae that are always trying to grow on everything in the ocean and would inhibit the blazingly speedy growth of juvenile bull kelp! The bull kelp microbiome at Tatoosh becomes more species rich toward the tips of the blades as the tissue grows and ages. Like an old field in the midwest, there is a sequence of species, a succession, along the blade of bull kelp. The relationship of bacteria to kelp is mutually beneficial with kelp receiving the microbial nitrogen boost and the microbiota getting organic carbon from the kelp.

This new knowledge of the diverse microbiota associated with kelp beds only amplifies our wonder at the complexity of interactions that is a healthy kelp forest. It makes us appreciate the tiny organisms responsible for keeping the bull kelp productive which means slick and smooth. Nothing feels more wonderful when snorkeling in a bull kelp grove than to run a gloved hand up that slippery stipe and around that glossy bladder.

Resources

This is just the beginning. Please go to our Washington Resources Page to learn more about the kelp work being done in this region.