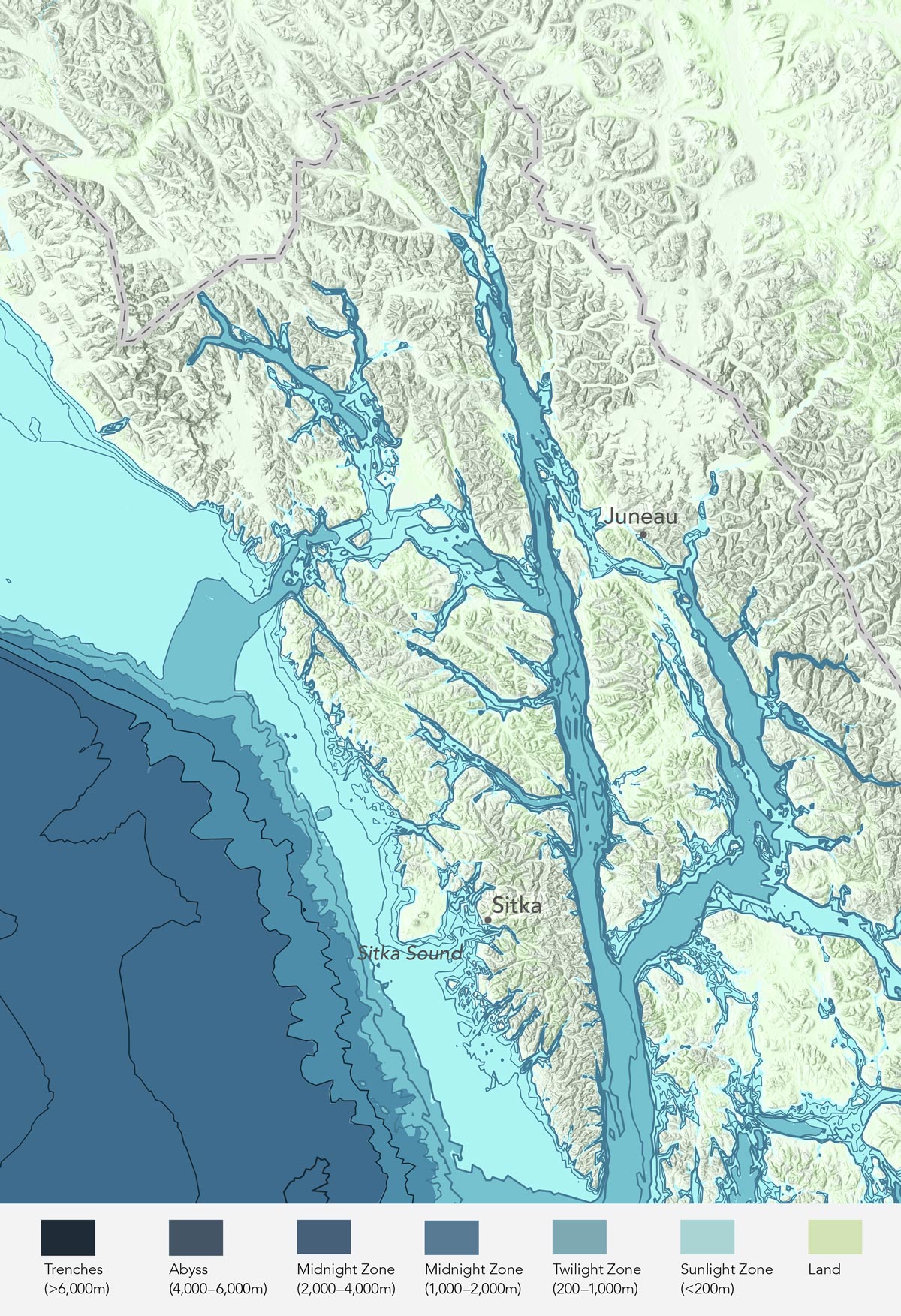

Bull kelp is very happy in Southeast Alaska, the funny panhandle of the United States that sticks down into Canada. Like British Columbia, there are countless straits, waterways, and thoroughfares—thin passageways of water between the thousands of islands that make up this unique stretch of coastline. As you move towards the poles the difference between low tide and high tide gets greater. Near Juneau, the capital of Alaska, accessible only by ferry or plane, there are twenty-five foot tides! This means an enormous amount of ocean water is pulled through each of these constricted passageways, first one direction and then the other, in the same twelve hour tidal cycles as everywhere else. And, being farther north, the ocean being pushed around is cold and nutrient-dense making this complex coastline classic kelp country. As the fast-growing bull kelp uses up the nearby ocean nutrients, a fresh supply is brought in on each tide, sustaining its remarkable single year of development.

Bull kelp beds here are abundant, healthy, stable, and in many places expanding. The infinite types of shoreline presents the opportunity for bull kelp to find its preferred habitat: protected or open to swell, near fresh water glacial output, or a river estuary (either of which bring added nutrients into the nearshore environment), rocky bottom or more cobbled.