The BC coastline’s interaction with the Pacific Ocean is endlessly complex. The jagged outer coast of Vancouver Island faces the wide Pacific directly while its inner shore flanks a web of narrow waterways and straits running between countless islands that connect the Salish Sea to the archipelago of Haida Gwaii, itself replete with rocky nooks and crannies facing both outward and inward. The Pacific infiltrates the mainland edge of British Columbia with deep fjords and by currents running back and forth around thousands of marine islands. If one stretched out the coastline of British Columbia it would extend for 15,985 miles or 25,725 kilometers. The magnitude of this varied algal habitat is mind boggling. Most of the waters adjacent to this extensive coastline—with cold, Pacific waters churning with waves or strong current—is host to bull kelp. Bull kelp is a flow hound; it loves the small passageways between islands where ocean water is forced through first one direction and then the other, bringing fresh nutrients with every turning tide. Bull kelp’s exuberant growth quickly uses up the nutrients in surrounding waters, so the influx of new, nutrient-rich ocean water is essential for bull kelp’s continuous success through the season.

British Columbia

“The diversity of kelp on BC’s vast coastline is unmatched, and provides unique opportunities for research and restoration.”

Central British Columbia Coastline including the northern tip of Vancouver Island and the southern tip of Haida Gwaii.

Its stipe can stretch up to 30% to give with strong water dynamics.

On the open coast this churning of nutrients might come from dynamic wave action. In the interior waterways of British Columbia and Puget Sound it comes from currents squeezing through deep channels between land masses with rocky shore. It is the dead end waterways in BC where the ocean does not have an outlet and flow is reduced that suffer the repercussions of a warming ocean and kelp beds are disappearing. This is apparent in the Broughton Archipelago. Where flow factors combine with newly re-establishing sea otters, (and the removal of large fish farms!) the bull kelp is healthy and salmon are returning; the inlets show less healthy kelp. But there is so little data to judge. Maycira Costa from the Spectral Lab at The University of Victoria is pairing with local First Nations to map these beds, make a record, and see what the future brings.

Sea Otter and Sunflower Sea Star: Are They Here?

Yes, sea otters are in some parts of BC and re-populating new areas.

Sea otters in BC have repopulated about a third to half of their historic range in the extended coastline of the province with about 8,000 mature animals as of spring 2022. After the last otter was shot off of Vancouver Island in 1929, there were no otter as predators on the BC coastline and invertebrate populations of sea urchins, clams, crab, and abalone soared, a boon to fisheries and First Nations who found opportunity in the coastal abundance. From 1969–1972, because of the impending nuclear tests in the Aleutian islands and fear that the blast could decimate the existing residual population, 89 otters were translocated from both Amchitka Island and Prince William Sound to Checleset Bay on the west coast of Vancouver Island. With abundant prey, otter populations soared, growing at first by 20% per year and then slowing to 8.7% per year, but did not spread to the entire coastline. Today sea otters cover about 33–50% of its historical range along the complex BC coastline. They have recently recolonized the Broughton Archipelago.

While kelp and algal populations rebounded with the sea otter/urchin predator/prey relationship re-established, The Kyuquot, a First Nation community down the coast from Checleset Bay, were not happy, watching their subsistence foods be eaten by otters, a species protected by the federal government. Having no control over the situation is a terrible place for Indigenous communities to find themselves, a situation repeated over and over again in both coastal BC and Alaska. As otter populations have grown in British Columbia, and First Nations have dug into the archeological record and deep knowledge of their relationships with otters, it is clear that humans and otters existed together in deep time, with humans managing the otters for their own foraging grounds to remain productive. Anne Salomon mentions: “far from dominating their historic range, otters were likely distributed in patches along the coast, separated from shellfish beds and the human settlements that relied on them.”

There are sunflower sea stars in BC. It depends where you are.

Sunflower sea star populations in BC are on the rise. They were decimated by sea star wasting disease which has persisted in the system since 2014. The Multi-Agency Intertidal Network (MARINe) September 2023 update begins: “When we first began seeing diseased sea stars during summer 2013, we had no idea that this epidemic would still be prevalent ten years later. While the level of sea star wasting (SSW)... is much lower now compared to the dramatic loss of sea stars that occurred in 2013/14, the effects have been lasting.” Despite this, Pycnopodia numbers are climbing, especially in colder ocean environments. A recent (September 2023) anecdote from the Broughton Archipelago described “plenty” of sunflower sea stars.

In Haida culture there is a story about the bull kelp. Hlkáam is a mainstay to the nearshore ecology of Haida Gwaii and to the culture of the Haida people. Nereo’s long, often uniformly thin, stipe would be collected and oiled—to stay malleable—and knotted together to make long proficient fishing lines. To make halibut fishing hooks a young wood section would be lashed to a piece of bull kelp stipe to follow its organic bend, the moisture of the stipe allowing the wood to hold the rounded shape of a large-scale fishhook. In 1905 John Swanton recorded myths and texts translated from the Skidegate dialect used by the Haida First Nations peoples of Haida Gwaii. He recounts one story that involves a two-headed bull kelp:

Two-headed bull kelp collected by Alex McClean, Pt. Reyes National Seashore.

“The son of a village chief has gambled and lost his father’s entire village. He runs away and floats away from the village on an enormous cedar beam. After a couple of days floating about in calm water he runs into a two headed bull kelp and hears a voice calling. It is a voice from under the water. He grabs the heads of the kelp and follows the stipes, like a double headed house pole down to the ocean floor. There he is invited in to the house of his ‘powerful grandfather’ who says, ‘you came floating about in search of me as soon as you had lost your father’s town.’ He fed his grandson and prompted him to find some appropriate wood to make two gambling sticks. One the wise grandfather inscribed with an otter the other with a young otter. These sticks the grandson took back up to the town and won back his father’s people and town.”

While the story itself is steeped in process and gambling details, ethnobotanist Nancy Turner interprets the two headed kelp as believed to mark the entrance to a supernatural world under the ocean where wisdom is found and brought back to the surface.

A two headed bull kelp is rare to find but not unheard-of. While we can conjecture what DNA glitch or environmental wound created the mutation of two pneumatocysts, they can be an occasional sign. The double headed kelp is beckoning us into its world, to seed us with its wisdom or the wisdom of the ocean around its holdfast. Perhaps it is the voice of the laughing grandfather who sees us having gambled away our town, our planet, saying "here…here is an alternative way to gamble and win it back."

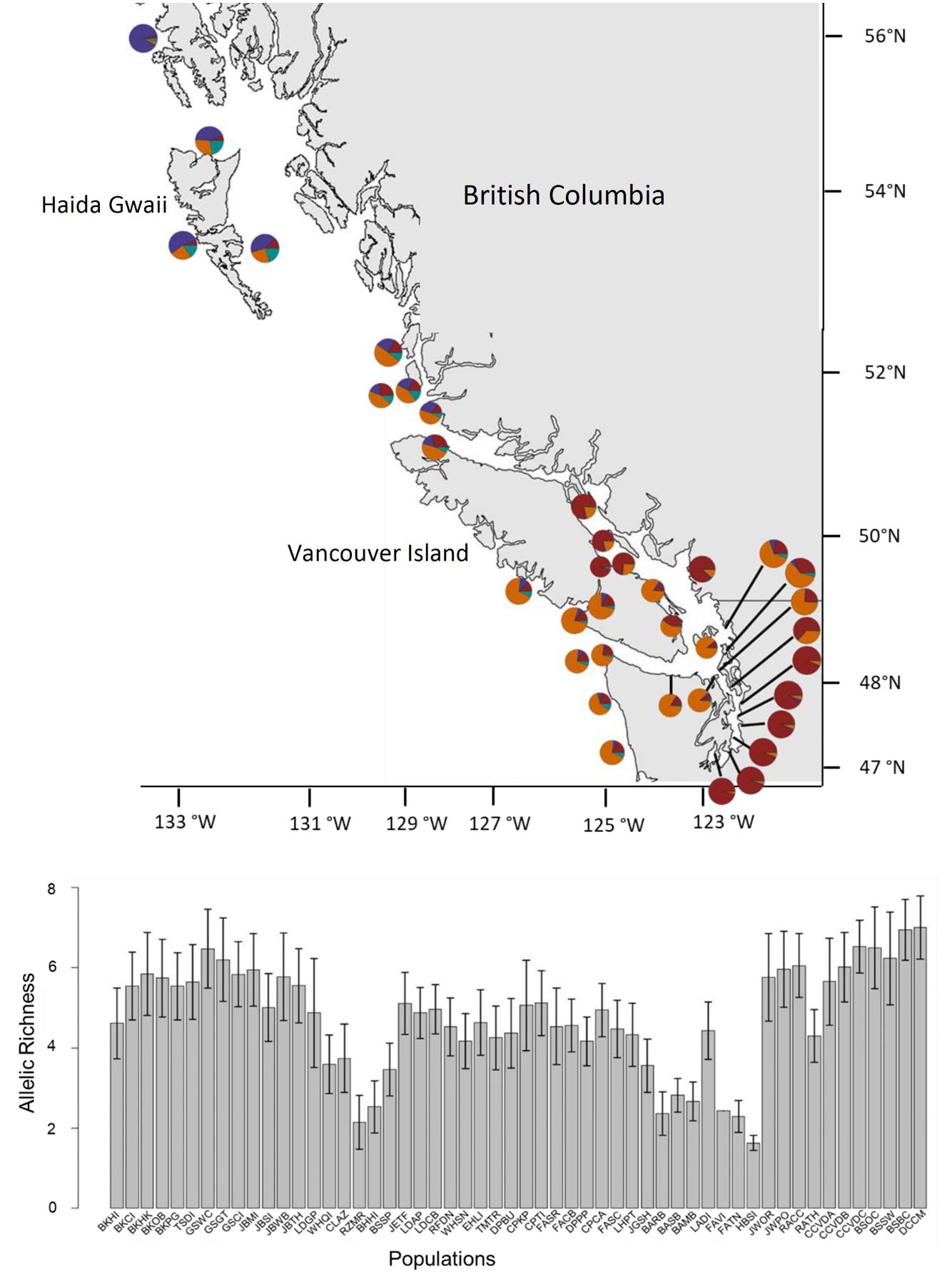

Allelic richness of Nereocystis luetkeana as mapped by Lily G. Gierke, 2019 working in the laboratory of Filipe Alberto, University of Wisconsin Milwaukee. 52 bull kelp sites (north to south going left to right) were surveyed with Squaxon Island WA (HBSI) showing the least diversity indicated by the shortest gray bar and the almost singular coloring of the circle. Highest genetic diversity in the region was found in three sites on Haida Gwaii (GSWC, GSGT, GSCI), showing tall bars and multi-colored circles with components from both Alaska kelp beds and lower BC kelp beds.

The Islands of Haida Gwaii (Xaayda Gwaay), and the surrounding waters are a pocket of non-glaciation along the BC Coast. For this reason it has some of the most genetically diverse bull kelp beds of the region. The bull kelp there had thousands of years longer to evolve and mix than the kelp in the scoured fingers of Puget Sound nearby. This genetic diversity implies resilience, access to more traits that might allow it to withstand different stressors such as warming oceans or more or less acidic or salty waters, perhaps more or less attractive taste to urchins. When gene mixing happens from populations above and below it, each bull kelp bed acts as a stepping stone to sharing alleles (alternate forms of genes) with adjacent kelp. As bull kelp populations shift and some kelp beds disappear, along with them goes genes to be mixed with populations nearby—the stepping stone disappears and the beds on either side of it become isolated and less able to mix genes. Extensive kelp mapping and surveys around the many islands and bays of British Columbia, Washington and on down the coast are discovering certain kelp beds radically diminished or gone, especially those without terrific flow and current. Isolated kelp populations, such as the one at Squaxin Island in the south of Puget Sound, have greatly diminished allele richness with fewer genetic options for, say, resisting higher oceans temperatures.

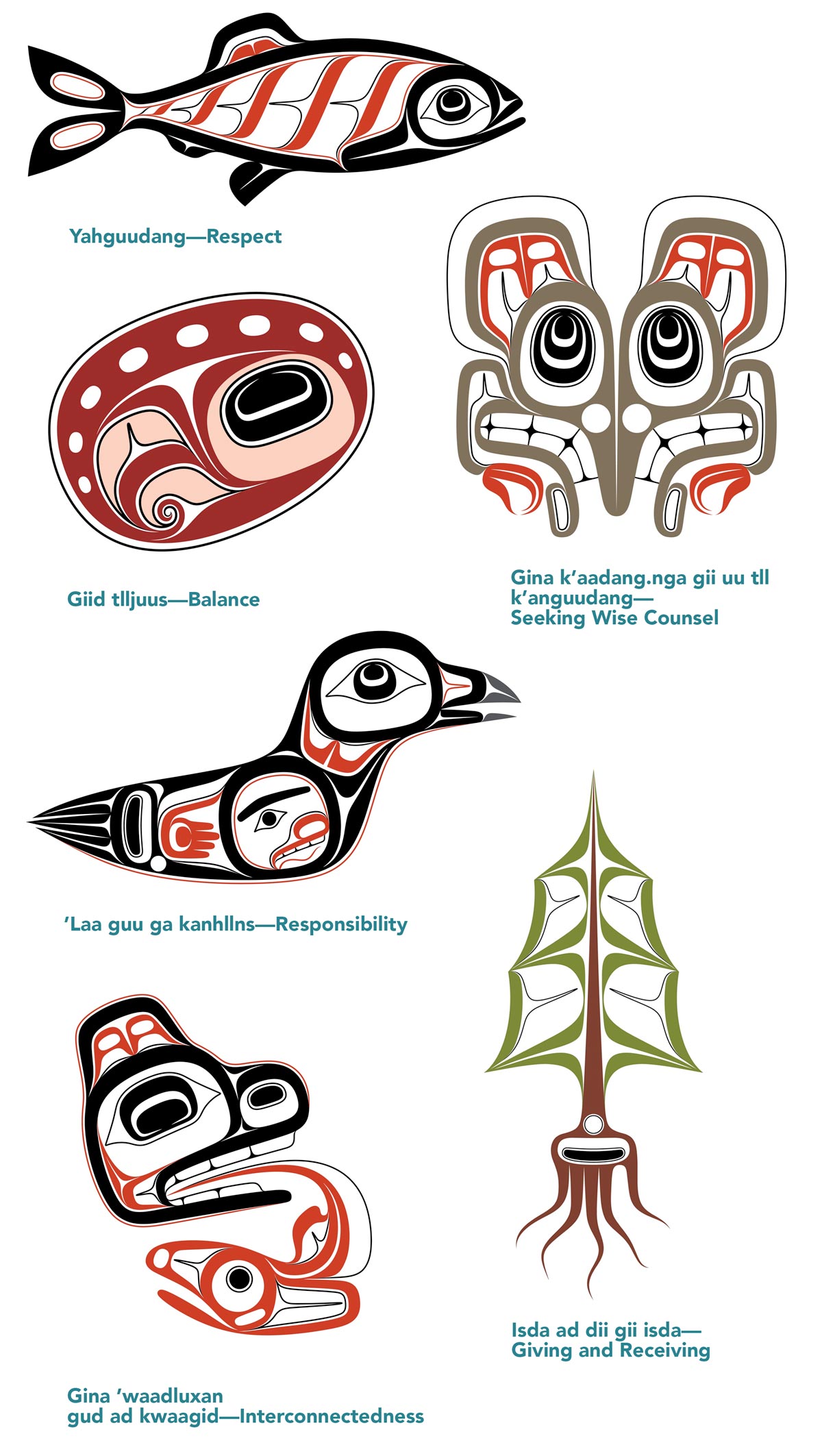

Haida ethics and values as guiding principles: Excerpted from Gwaii Haanas Gina ‘Waadluxan KilGuhlGa Land-Sea-People Management Plan 2018.

The kelp restoration project at Gwaii Haanas, at the southern tip of the Haida Gwaii archipelago, is notable for its guiding principles based in Haida ethics and values, as well its cooperative management between the Haida Nation and Parks Canada.

The restoration project's goal was to mimic sea otter predation to restore kelp. The removal of urchin, (red, green and purple) was done by a diverse group of divers from 2018–2019 in anticipation of kuu—sea otter (Enhydra lutris)—returning to this section of its ancestral territories on the BC coast. The 2019 and 2020 years showed differing levels of kelp recovery, and highlight that ocean conditions will vary and the recovery process is not linear. The 2022 and 2023 kelp recovery has been positive and gives great encouragement to these restoration projects. Long term monitoring and continued urchin management is essential.

Resources

This is just the beginning. Please go to our British Columbia Resources Page to learn more about the kelp work being done in this region.